The Ballad of Black Batman

A tale of Twitter threads, heroic legacies, and how Marvel already did it better.

BY: RYANNE KAP

Photo courtesy of VT

When you hear “Batman,” what’s the first thing you think of?

Christian Bale’s jawline? Sad Ben Affleck? A meme from 2008?

All three of those examples have one thing in common: a white man. And I wouldn’t be surprised if you pictured that too. While Bruce Wayne/Batman has been around since 1939, he’s mostly been portrayed as Caucasian throughout his 81-year history. In the film adaptations, he’s remained exclusively white.

That hasn’t stopped fans from imagining alternatives. In 2019, a fancast of Daniel Kaluuya as Batman made the rounds on Twitter, sparking similar backlash from when Michael B. Jordan was rumoured to play Superman.

Before we unpack that, let’s talk about why the movies matter. Comics and TV shows are both important mediums, but movies are the most immediately accessible (and attention-grabbing) for most viewers.

So while DC Comics may be introducing a Black Batman this summer, much of the Twitter discourse is focused on Batman on the big screen, and how powerful seeing a Black Batman there could be. But with tweets like the above questioning the legitimacy of alternate casting, let’s explore what a Black Batman means.

Race is just one of the qualities that can inform a character’s perspective, but when it comes to creating idealized figures like superheroes, it’s important to consider what types of bodies we consider to be powerful—and, more importantly, what types of bodies we consider to be good. For iconic heroes like Superman and Batman, that type of body has been a white one. Yet simply making a character Black doesn’t solve the problem of how Blackness is being represented (or rather, underrepresented).

Whereas Superman is an alien from another planet (and thus could really be depicted as any race), there is something about Batman that seems inherently white. Namely, he’s an ultra-privileged billionaire with generational guilt.

Writer Jamelle Bouie explains, “[B]atman is the one character you would have to completely rewrite to make black, since his background depends on him being an old money Rockefeller Republican type.”

As Marc Bernardin writes in The Hollywood Reporter, “Bruce Wayne has to come from old money because he has to feel the generational guilt that comes with being a Wayne [...] Bruce Wayne has to be white because that kind of legacy and wealth don’t exist in the African-American community. (Yet.) For that character to be true to who he is, he can’t be anything else.”

Photo courtesy of Geek Expression

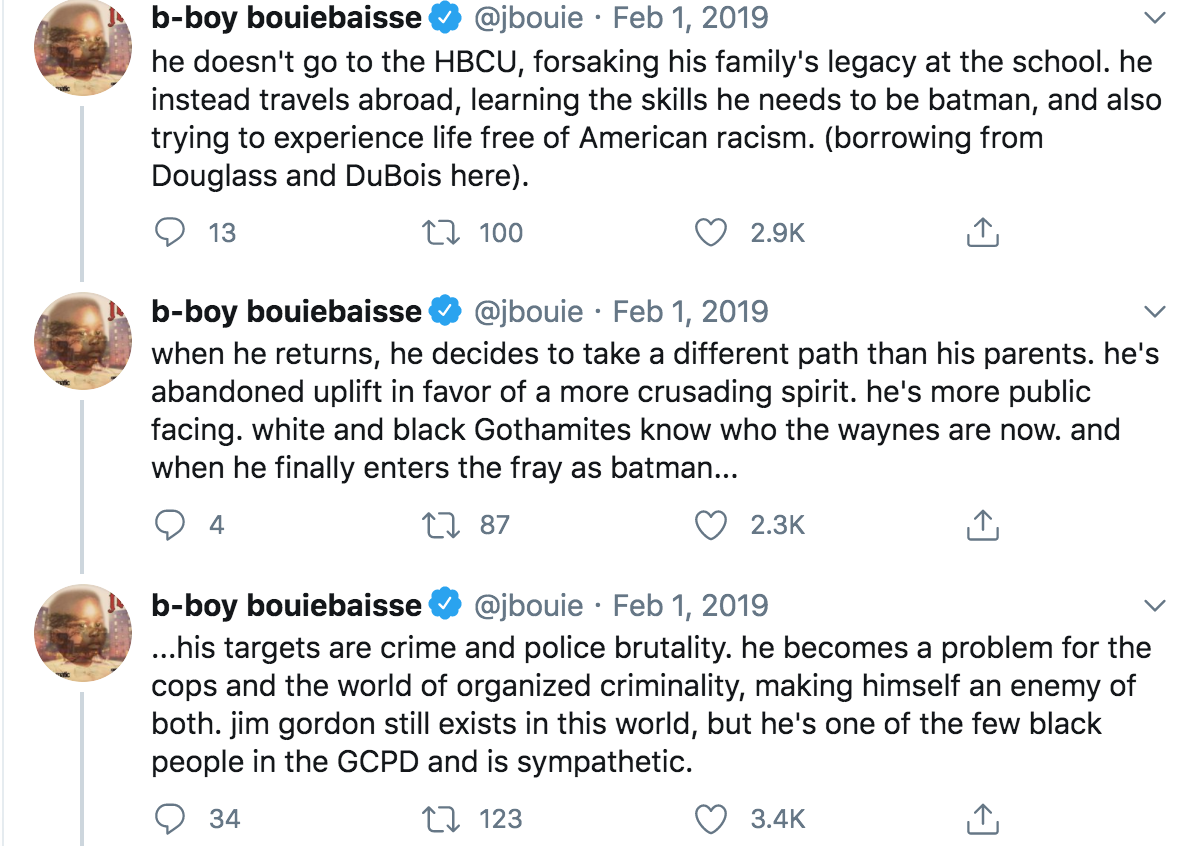

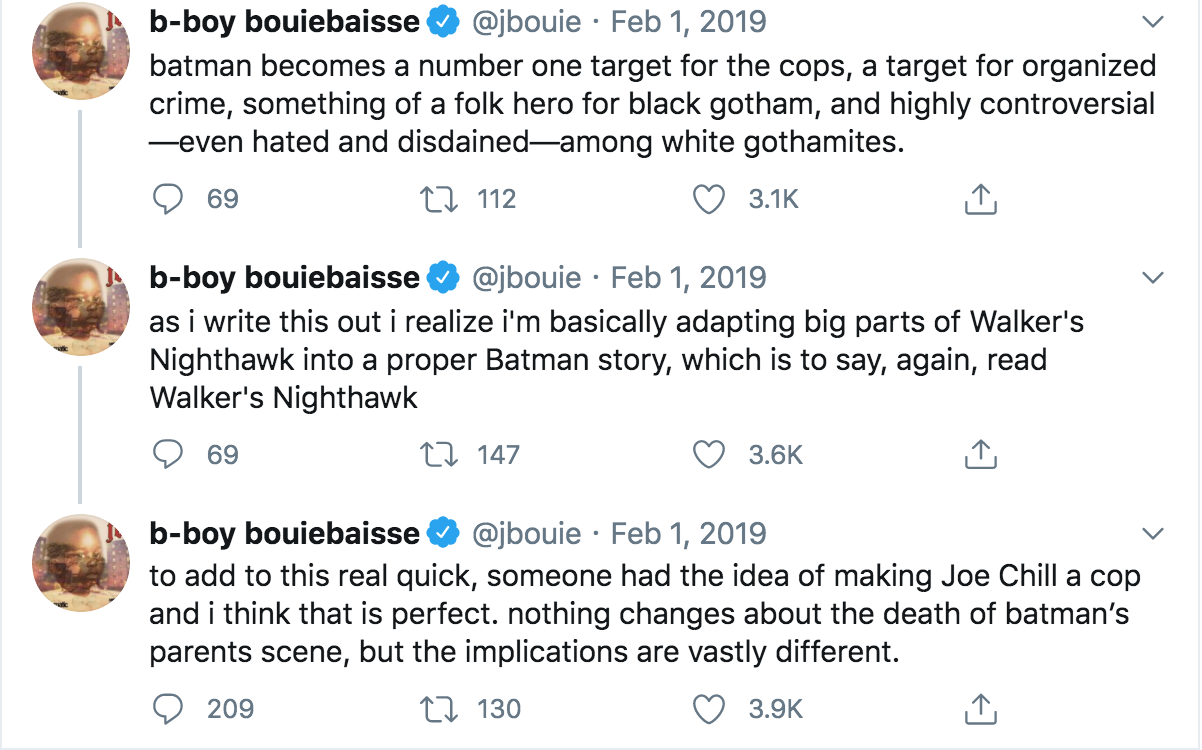

Of course, it’s not impossible. Following his tweet about a Black Batman, Bouie fleshed out the idea in a Twitter thread that reimagined him as the descendant of prosperous, free Northern Black folks.

The cause of his parents’ death remains the same, but when a young Bruce calls the police, they’re apathetic in helping. This leads to him developing a righteous anger at racism, eventually becoming a Batman who targets crime and police brutality. But for Bouie and others like him, a Black Batman is only imaginable with changes that aren’t just surface-level.

Casting a Black actor as Batman without changing any other elements of the character would do a disservice to actual Black experiences. Casting Steve Buschemi as Black Panther would do that and erase what makes the character a unique and positive hallmark for Black representation. In Ryan Coogler’s Black Panther (2018), Blackness is not just incidental to the story; it shapes Black Panther’s arc as a hero and informs his identity in a thoughtful, nuanced way.

It’s what also makes him the perfect answer to the quandary of a Black Batman.

Photo Courtesy of Monomythic

Like Bruce Wayne, T’Challa has a costume based on an animal, plus a host of cool gadgets at his disposal. He also has privilege, though in a radically different way. As king of an extremely powerful and technologically advanced nation, he is canonically the wealthiest superhero. In a country untouched by colonialism, he’s also never dealt with systemic racism and oppression to the extent that his Black American counterparts do.

But Black Panther isn’t just a Batman substitute (some even argue he’s more Batman than Batman). He’s a character whose story contains similar elements, but within an entirely new and unique context based in Black experiences.

Black Panther (2018) is a striking Afrofuturist exploration of the effects of colonialism and the possibilities of Black power and excellence outside of it, but it also takes care to consider who gets left out of the narrative.

Wakanda is a country that never saw its people enslaved and displaced, but also never intervened to help anyone else. This isolationism, and T’Challa’s role in determining its course for the future, is at the heart of the ideological argument between him and his nemesis, Erik Killmonger. Killmonger is the son of a Wakandan prince but grew up in Oakland, California, where he witnessed systemic racism and oppression as a Black man in America. Embittered by his experiences, Killmonger believes the solution is to colonize the colonizers, to “beat them at their own game.”

Photo courtesy of Black Panther

Though he’s positioned as the villain, Killmonger is right when he points out that Wakanda has been complicit in global injustice by doing nothing to protect Black people. Of course, T’Challa’s love interest Nakia points this out as well, but Killmonger gets the flashy fight about it.

It’s a unique dilemma distinctly rooted in the problems Black folks face. As Alex Abad-Santos writes for Vox, “Black Panther isn’t satisfied with just being a movie featuring a black superhero. It strives for something more complex than right and wrong and more powerful than a vibranium-laced fight scene.”

We don’t need a Black Batman when we have stories like Black Panther, which offer positive and complex Black representation. Instead of just slotting Black actors into stories made for white ones, it’s much more powerful to give them new narratives that not only show them on the screen, but actively explore and celebrate Blackness.

It’s also proven to be a good business move: Black Panther made $1.3 billion worldwide and is currently the fifth most commercially successful superhero movie of all time. Audiences clearly support diverse films, and with Black Panther 2 slated for release in 2022, more of them are on the way.

I hope Robert Pattinson can keep up.