“I hate my nose, wbu?”

Filipinx roots run deep, but apparently only white blood is beautiful.

BY: RACHEL GUANLAO

Art by Daniel Gomes // THE UNDERGROUND

At the age of four, I was encouraged to pinch my nose and sing “Twinkle Twinkle, Little Star” in hopes that my nose would “sharpen up.” At ten, I found online that the nose is built up of cartilage, not bones, which gave me hope that it could actually change its shape. At age twelve, I ordered a nose pincher off eBay so that I wouldn’t have to undergo the tedious task of pinching my own nose. And now, from the day I started dabbling in makeup to the days I’ve become a Sephora “Very Important Beauty Insider” (VIB), I’ve contoured my nose to make it look sharper, smaller, and more defined.

For the longest time, I couldn’t understand why I had such a hateful relationship with my nose. Was it because I was conditioned to keep pinching it all the time? Was it because my nose was actually ugly? Or was it something else? Something I haven’t been paying close enough attention to?

In 2018, I took a trip back to my homeland, the Philippines. As someone who couldn’t afford the luxury of visiting regularly, I was excited to see my relatives after 13 years since my family’s departure to Canada. It was a joyous occasion; I was kissed by the hot sun and embraced by the cool, salty waves of the sea. I could hear my family laughing in the background as I laid on the beach cherishing the sheer bliss of that moment.

After our beach trip, I was enviable by Western standards. I had turned three to four shades darker with my tan, and suddenly my Fenty 300 foundation was way too light. I went to an SM Megamall, which was larger than anything I’ve ever seen in Toronto, and I browsed the wide array of department stores, makeup stands, and counters to find my perfect shade. I was appalled by the fact that I had consistently been one of the darkest shades, only because I didn’t find myself ‘dark’ at all—so why was I the last of the shade range? Only then did I account for the aisles of skin-whitening treatments in supermarkets, and realize my since-childhood desire of a slim nose was a lot more than just aesthetics.

When I was getting my nails done, the nail technician said to her assistant, “Maganda siya kahit hindi siya maputi,” which means, “She’s pretty even though she’s not fair-skinned.” And all I could say was, “Thank you,” because it’s part of Filipinx culture to be polite to strangers (particularly elders), and at that point in time I still didn’t understand the deeper, underlying issues behind that statement.

It was an unsettling and perplexing feeling to realize that I lived in a bubble. While my complexion was always accepted and embraced in Toronto, I was considered ‘dark’ in my own country and by general perception, it wasn’t a good thing. In fact, it appeared like it lessened my beauty. I had thought, “Maybe I did tan a little too much?” but that phrase alone went against the diversity and shade inclusivity that I wanted for others, and it didn’t feel right. I thought about my nose too, and then I remembered Miss Universe.

Pia Wurtzbach. Image by: The Miss Universe Organization

Catriona Gray. Image by instagram @catriona_gray

In 2015 and 2017, I was incredibly proud of my country. I went to my cousin’s house both times to watch Miss Universe, where Miss Philippines—Pia Wurtzbach and Catriona Gray—reigned supreme. As beauty is subjective, Miss Universe isn’t an accurate portrayal of universal beauty, but winning the title means that some people may find you to be. As their surnames suggest, Wurtzbach and Gray are only half-Filpina; Wurtzbach is half-Dutch, while Gray is half-Australian. It was discomforting to see that ‘Philippine beauty’ was depicted through a tall, medium to light-skinned complexioned woman with noticeable Eurocentric features, such as deep-set eyes and a taller nose: traits that you will not typically see among the majority of Filipinxs. In addition, some of the most famous Filipina actresses, such as Liza Soberano, Marian Rivera, and Anne Curtis, all share the same Eurocentric features because only one parent is Filipinx. In contrast, darker-skinned Filipinxs were always perceived to be the funny ones; the comedic relief.

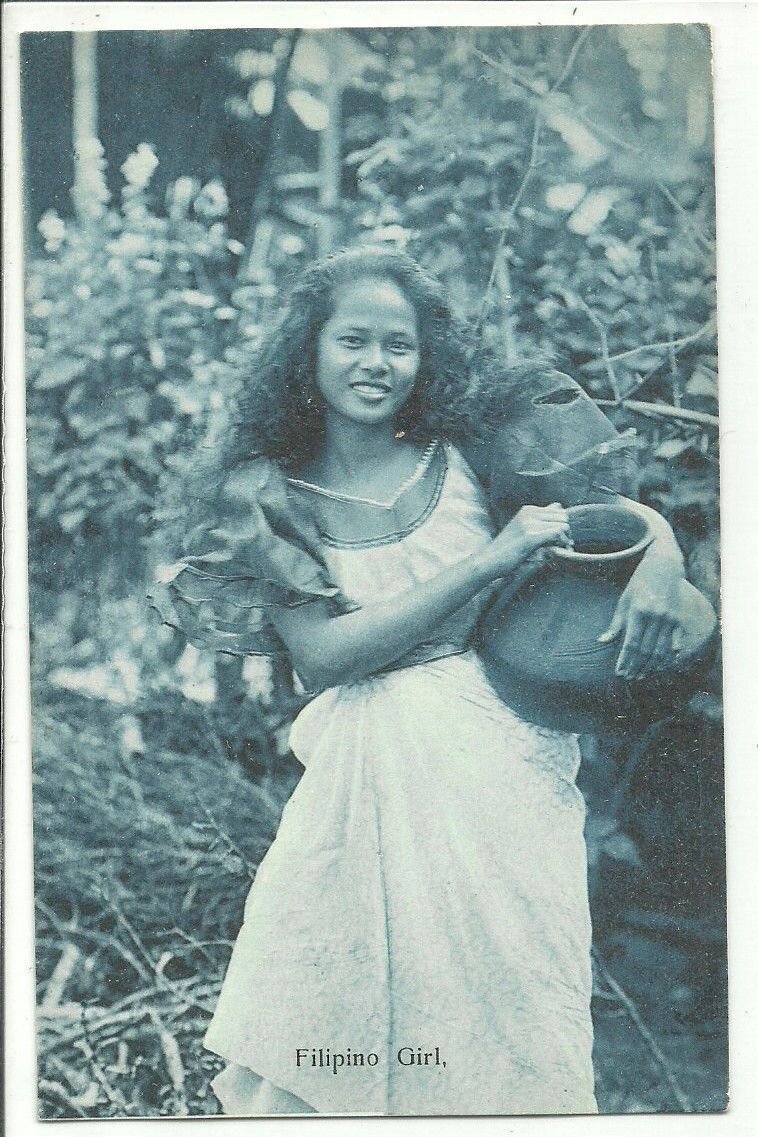

Old photographs of what Filipinas look like in contrast to the representation in mainstream media.

“Filipino Girl” courtesy of Pinterest

Photo by James Tewell

Photo by John T. Pilot

Colonial mentality is the internalized attitude of ethnic inferiority as a result of colonization and corresponds with the belief that the cultural values of the colonizer are superior to one’s own. The Philippines was a forceful creation by Spaniards in 1542 when they claimed the islands as their own. In fact, the name “Philippines” means “islands of Felipe,” in tribute to King Philipp II of Spain. After approximately 333 years under Spanish rule, power was given to the United States until 1946 when they granted the Philippines full independence. The Philippines has a long history of colonization, and as Filipinxs, it has translated into how we perceive beauty.

Metisses de Manille - “Mestizas of Manila”

Photo from Lucon et Palaouan (six Annees aux Philippines), I-XII (1886)

Miss Philippines winning Miss Universe is damaging because in the two times they’ve won in the decade, neither Wurtzbach or Gray were a real representation of Filipinx features. On the other hand, having the illusion of representation only strengthens the colonial mentality in the Philippines. As a Filpina-Canadian, I thought it was bad enough that my country praised Filpinxs who had Eurocentric features, but to see them win global competitions was as terrifying as it was gratifying. Gratifying because although it is still misrepresentation, at least we actually got someone representing the Philippines in mainstream media. However, it was just as terrifying to think of all the impressionable Filipinx children and teenagers who see this and think “this is what our beauty should look like,” and that even non-Filpinxs seem to agree.

It’s crazy to see how in Western beauty standards, ‘exotic beauty’ has been fetishized; tan skin is in, and thick, black hair is beautiful. Yet all throughout Asia there is a constant desire to be whiter, or at the very least, white-looking. When I hear Filipinxs talk about their background, they always say, “...because we were colonized by Spain.”

“I have Spanish blood,” they say.

While it may be true for a large population of Filipinxs, that phrase is intended to be complementary to oneself. This is why colonial mentality continues to prevail despite 74 years since independence; because being more White, looking more White or appearing to be so is associated with power and beauty. White foreigners are treated specially in the Philippines, and English is the language of the rich and well-privileged. In addition, not being able to speak English indicates that you’re poor or lacking education. But just as there is beauty in power, there is beauty in our roots.

Regions within Philippines. Courtesy of Wikipedia

With over 7,600 islands, the Philippines is home to many Indigenous tribes that have persevered through colonization. Upon researching tribes who’ve kept their cultural identity, you will find that there is so much more to the Philippines than the white-washed beauties in media representations.

There is the Igorot tribe of the north, who built the beautiful rice terraces more than 2,000 years ago.

Banaue Rice Terraces. Photo by Thanhhoa Tran

The Lumad tribe of the south, who are known in particular for their tribal music and instruments.

There are the Badjao sea tribes who live in houseboats, the Palawan tribes who live on mountains or lowland dwellings, and the Aetas, who are one of the earliest known inhabitants of the Philippines.

A Badjao child rowing a boat. Photo courtesy of Idome via Shuttershock.

A Palawan Tau’t Bato Tribe girl making a hunting device to catch her family’s dinner. Photo courtesy of Jacob Maentz

A group of Aeta people. Photo courtesy of Nico Anastacio

These are only a handful of the many Indigenous tribes in the Philippines, but a common feature among all of them is their tan skin and flat nose. Yet all the different tribes, although they share common features, all look distinct and different. There was such a diversity of facial features and characteristics of pre-colonial Philippines depending on which region you were from, but now only a ‘certain’ look is considered beautiful, and it doesn’t include these Indigenous communities.

Even until now, Indigenous tribes have been discriminated against for their traditions, customs, and appearance. They don’t even get reserves. The reason they’ve still lived through colonization is because upon the first arrival of settlers, they hid in the mountains, islands and dwellings far away from the colonies. However, a lot of these tribes got left behind by civilization, having no access to higher quality education because they chose to keep their traditions. Is this what it is then? They had to make a choice between assimilating to a culture that was moving forward, or to continue in hiding to preserve their own culture.

On the other hand, for the tribes who didn’t hide, everyone got mixed up. That’s when the terms “Mestiza, Chinita, Morena and Negra” became something to identify Filipinx ancestry based on their appearance. It would be hard to find a “pure” Indigenous Filipinx in Manila because of the history it holds with regards to colonization.

The Indigenous tribes who inhabited the Philippines first are not only seen to be the opposite of what ‘beauty’ is, but also uncivilized, which is a damaging thing that the colonizers did. They made the Indigenous people feel like they needed them in order to advance in life. Having done this research has shown me that these deep-rooted issues spread even further than just beauty standards, but societal perceptions of certain people.

Colonial mentality has shaped the Philippines, and more noticeably, shaped their beauty standards. I write this not to spread hate for colonization and its consequences, but to embrace the Filipinx roots I hated as a result of it. To embrace my easily tanned ‘morena’ skin, flat nose, and short stature because even if they don’t adhere to the current beauty standards, they are beautiful simply because they are a physical representation of the Filipinx people.

There are changes and movements however, in embracing Morenx skin, and being more accepting of these Indigenous tribes, but there is still a lot of work to be done. There is still a general negative perception about these tribes, that they are people to be pitied. Due to their lack of advancement in the modern setting, they have had to commodify their culture in order to make money, like how foreign travelers will get a tribal tattoo from Whang-od, or go to Baguio and dress in Igorot clothing to take pictures.

Whang Od, a 103-year-old tattooist of the Kalinga tribe uses a thorn from a pomelo tree as a needle. She tattoos spiritual and symbolic designs and requests a fee to help her village. Photos courtesy of “I am Not a Tattoo blog”

It seems almost unbelievable that trying to unpack the beauty standards in the Philippines led me to discover the harsher treatment towards its own natives. Colonial influences have been deeply ingrained in our modern culture, language, and food today, set apart from the white-washed beauty standards I began to write this about.

A part of me growing up wished I was mixed with white, too; down to my nose, always wanting to dye my hair blonde, and wearing lighter-coloured contacts in high school. I hate to say it, but it’s true.

But I know there are more people like me. There are people who’ve been shamed for being too dark, for not having the ‘perfect’ nose, for wishing for lighter-coloured eyes and lighter-coloured hair, wishing for bone-straight hair at the price of our waves or curls, because our natural state isn’t good enough in our cultural beauty standards.

But I encourage you, as I did myself, to see the beauty within the cracked lines of the pavement, because there’s something so captivating about breaking the slab of concrete to reveal the life that grows underneath it. Even if we cannot conform to the ‘concrete’ that is our beauty standards, underneath the hardened tar is another type of beauty that cannot be manufactured. If you are anything like me, I encourage you to embrace the lack of ‘Whiteness’ in our appearance because it is a physical reminder of our rich cultures and heritage. Embracing these features not only makes us unique and special, but it also reclaims power back into our roots.

These are things I’ve learned from it so far, but that doesn’t mean the work myself and others have done is finished. Embracing our features is only one part, but we must continue to speak up so that these beauty standards don’t proliferate. We must encourage real representation, and grow to see that the post-colonial world we live in isn’t restricted to just that; that we may also respect the indigenous peoples of the Philippines and their traditions, and their appearance. I hope that in the future, children won’t be taught to change their nose structure, teenagers won’t have to whiten their skin, and these Indigenous tribes and darker-skinned people won’t be seen as having lesser value just because they don’t conform to the standards of one society. I know it is not a bleak future, because progress has been made and hope still exists.