Why Do We Keep Wanting to Change the People We Love?

If love is an uphill battle, do we continue fighting to keep our toxic loved ones, or do we let go for the sake of our own peace?

BY: RACHEL GUANLAO

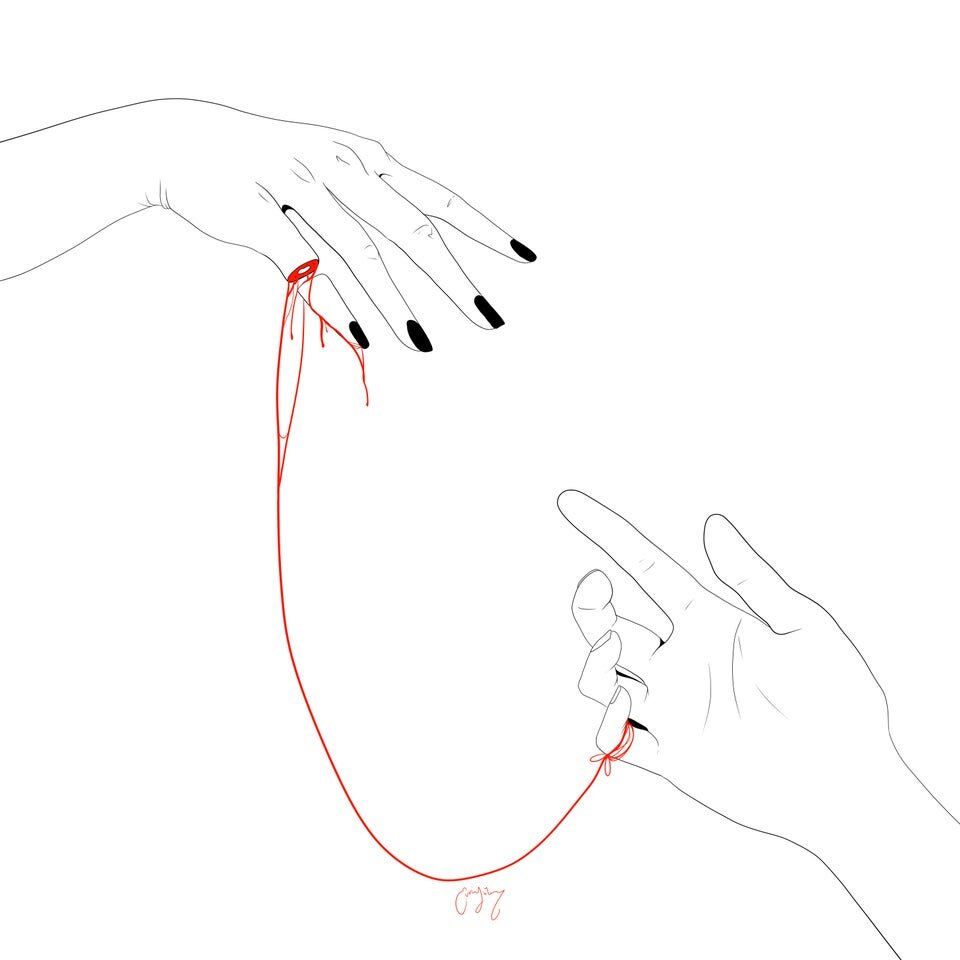

Art by Purinnie

I googled “can we change the people we love?” before I began brainstorming what to write. Unsurprisingly, what I found were countless magazine articles that either showed the good changes that come with love, the horrible consequences of changing yourself for someone else, or both. As love is unique to one’s own experience, it is difficult to have this discussion in a way that is fair and balanced. Regardless, I believe it’s worth exploring because love is a driving force that brings people together-- but what do we do about the love that brings us pain? Or the very people inflicting that pain unto us?

“Every heart sings a song, incomplete, until another heart whispers back. Those who wish to sing always find a song. At the touch of a lover, everyone becomes a poet.” - Plato

Perhaps people can relate when I say I’ve dreamed of a perfect love—like the ones in old movies, songs, poems, and books. “To be a muse to someone,” I’d say with dreamy eyes, glittering with wonder. How could we not want that for ourselves? We all want to feel loved. We all want to feel happy. A lot of us crave a love we’ve never received. A lot of people never really received much at all. Yet is often the relief we find in love that makes the hate in this world a little more bearable.

Art by Zipcy

Love is always subjective. How I view love may be completely different to how you view it, but there seems to be common ground in how we can show it. I’ve consulted various religious texts to see what they each had to say about love. In Christianity, Judaism, and Islam, to “love your neighbour as yourself” is a common theme. In other religions, such as Buddhism, Hinduism, Taoism and Confucianism, the same message is presented, just a little differently. Do not do unto others what you would find hurtful and hateful to yourself. It is what’s referred to as the “Golden Rule of Reciprocity” and what’s to be reciprocated is love.

It amazes me how these religions are completely different from each other in terms of beliefs, morals, and values, yet a common vein between them is how we demonstrate love to each other. In all of these texts, love is described as selfless and compassionate—treating others how we’d like to be treated. But there is also something to be said about the contrast of what religious texts want us to show versus what we try to ‘stray away’ from—that this guidance is here so that we may not spiral into the evil counterparts of our very nature.

When it comes to love, it is important to remember that nobody’s perfect, and though some may dream of a perfect love, it is something we can never truly accomplish because of our human flaws. It’s a reminder that as much as we think about our toxic loved ones and what we could do to help them, sometimes we’re the toxic ones too.

Art by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

One of my earliest understandings of this was through the story of The Little Prince and his rose. The rose was too prideful to openly admit her own shortcomings. The little prince was too naive to understand the complexities of his rose. Both parties realized that they didn’t understand how to properly love each other and went their separate ways.

The rest of the novella details the little prince’s journey; the valuable lessons he learns along the way is what leads him back to his rose. He stumbles across a garden of roses who look exactly like his, and he soon realizes that there was nothing special about his particular rose on the surface-- but that she was special because she was his rose. He spent time taking care of her, and she made him happy.

Art by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry

“If someone loves a flower of which just one example exists among all the millions and millions of stars, that’s enough to make him happy when he looks at the stars. He tells himself, “My flower’s up there somewhere. . . .” But if the sheep eats the flower, then for him it’s as if, suddenly, all the stars went out. And that isn’t important?” (The Little Prince, Chapter VII).

Aren’t we all, in some way, shape or form, like the little prince and his rose? Similar in the sense that we’ve all felt suffering and pain because of the people we love, but different because we all have different roles we assume in our relationships.

In the end, there is always a lesson to be learned from both sides.

Unknowingly, the prince taking a break from his rose demonstrated the boundaries that must be implemented in respectful relationships, and the rewards he was able to reap from it: self-discovery, growth, and a newfound respect for his beloved rose.

Art by Shawna X

I know this is just one example, and love isn’t a one-shoe-fits-all arrangement. Love is a lot more complex than the summary I’ve presented and goes deeper than words can even explain. For some people, love includes tolerating abuse, poor treatment, cheaters, and unhealthy addictions. Everyone has their own story to tell, and I am in no position to mislead others into the “right way” of living their lives, but what I can do is interpret these stories and see where we can go from there. Love may be a choice in the sense that we are always choosing to love someone, but the little prince reminds us that those we choose to love are deeply ingrained in our lives because of the time we’ve spent with them, the sentiment of nostalgia and euphoric memories, and sometimes to our own fault, our attachment to them.

So, why do we keep trying to change the people we love?

As I ponder every scenario I can think of, all routes lead back to the thought that just something about them simply needs to change. In a way, magazine articles didn’t lie when they wrote of the beautiful changes that healthy relationships bring people, such as higher self-esteem and confidence. However, the very thought of wanting to change someone says less about the person we love and more about our own desires—a trait that has been considered the opposite of love as seen in the Golden Rule.

We all appreciate a good hero story. Dominating the plot of most high-grossing movies today, there seems to always be a hero to admire. I know this through the Hero’s journey—or “monomyth”—in literature, where the template for every good hero story (Star Wars, The Matrix, The Lord of the Rings) follows the same type of narrative people are drawn to. So what is it about us that makes us drawn to the same media that producers keep creating?

It’s the fact that heroes are not like other humans. They’re different—in a good way, and we admire that about them. In a commentary about “Why We Need Heroes,” Scott T. Alison and George R. Goethals explain that heroes reveal our missing qualities, save us in times of trouble, give us hope, and nurture us when we’re young.

We all strive to be like our heroes. When we’re young, sometimes the first heroes are our parents, firefighters, or Superman. In relationships, it feels good to believe that you are a hero for someone else, or that there’s someone out there who wants to be a hero for you.

Art by Jake Parker

Yet what may develop from this is something called the ‘Savior Complex’. The Savior Complex is defined as “a psychological construct that makes a person feel the need to save other people. This person has a strong tendency to seek people who desperately need help and to assist them, often sacrificing their own needs for these people.”

In wanting to change the bad habits or toxic traits of my loved ones, I realized that taking active measures for their change is a lot more self-absorbed than I had thought. By wanting to save someone, are we not assuming that we have the necessary tools, knowledge or resources to actually change them? Are we not telling them what they should and shouldn’t do? Be careful believing that we are enough to bring genuine change for people because if it were that easy, we would have no need to navigate the hurt and pain in our own broken relationships. Be careful, because as described in the inherent desire to be a hero, we end up sacrificing our own needs in exchange for what we can do for someone else’s change.

Toxicity is like a venom. It poisons our good qualities and makes it hard to nurture healthy relationships. It blurries our vision when making proper decisions. It reveals the evil in our hearts and consumes our thoughts. It is this very nature that religions and life philosophies have preached against for centuries. Sometimes, we’re unaware it happens because toxicity can be disguised in the form of love. Whether it’d be the comfort and security of it all, the fear of leaving behind memories, or never finding anyone else; wanting to change someone for the better really means wanting better for ourselves.

Art by Kisurando

Don’t get me wrong―wanting better for ourselves should be a standard, and we shouldn’t have to feel bad for that. But wanting better for ourselves by trying to change the ones we love is a different story.

By wanting to “fix” the undesirable aspects of a person, there is a sense of control that wants to be gained by the “fixer” using that specific person’s idea of better or “healthy”. That doesn’t necessarily mean the people who try to change their loved ones don’t have good intentions; it just means that conforming others to our own subjective ideals is also toxic for both people involved.

I do, however, believe that people can change as a result of the love they are shown. In the little prince’s story, we are shown a love that is relatable and the lessons we can learn from our quarrels. From the religious texts, we see how love is a defining element for how one should live, and that the most important thing is to show others love. In explaining the Saviour’s Complex, it reveals that wanting to change people is perhaps a projection of our own selfish desires; deviant from the selfless love we always hear about.

The true test of wanting to change someone, then, is not a question of how we can actually change them, but how we can show them a love that serves as a catalyst for change.

A 6-minute video called “What Love Truly Is” by the School of Life, sets insightful guidelines and advice on how we can show the selfless love we yearn for. And although love is subjective, there is still the universal language of charity, imagination, kindness, forgiveness, loyalty, generosity, and patience.

In the video, one of the main components of showing love is in our kindness. The example School of Life used was how fighters for social justice are so determined to make a better world that they denounce their enemies and feel certain of their cause. However, along the way, they have a habit of forgetting to be kind. With the current fight against racism and injustice for Black lives predominantly in America (yet systematically, everywhere), some of the advocacy we can do is talking to our families, friends, and strangers and showing them why their perspectives are damaging. But we must do so with kindness and love if we truly want them to listen. With the pain and hurt being expressed in riots and protests, remembering to spread love despite adversity is the light that enables listening ears.

It is, however, a bit damaging to assume that simply showing love to our toxic relationships can salvage them, especially with regards to abusive partners. Let’s make it clear: people can change, but only if they truly want to. Nobody can do it for them, and it’s a challenge some people can't envision for themselves, but it’s worth it to try. To support healthy decisions, to take note of our own faults, to be compassionate and empathetic to one another while still maintaining healthy boundaries.

Art by Purinnie

Letting go for the sake of our own peace is a boundary we must conclude for ourselves. To let go means that the hope of someone becoming better is not within our own reach, but that doesn’t mean we have to stop showing love for them. When couples break up, a common line I hear is “I’ll always have love for you,” as we continue to tell our friends the horrible things they did to us. But we must remember that if we truly wanted someone to change in the first place, we need to actively fight against the hate that festers our thoughts and show them a love they never truly received. I find that toxic people always have unaddressed trauma. Encouraging them to rise above it and find success, even without our presence, is something we can do for the people we love. After all, are you more likely to listen to an angry, hateful person insulting you or your choices, or to an understanding and empathetic person offering constructive criticism?

We may not be able to change the people we love willingly, but people can change. People can truly change because of the love they’ve received, the love they never expected to give, and the love they learn to show themselves. Sometimes showing love is taking the time to understand the person’s traumas, love languages and attachment styles. Sometimes showing love is praying for people who need it. Sometimes it’s offering to pay for lunch after a counselling session. People can change, even our toxic loved ones, but it is not an overnight occurrence. It is a gradual, often long and slow process that requires a lot of love from our end as well. If love is an uphill battle, we must remember that some battles are worth continuously fighting for, some battles we must surrender, but we mustn't forget why we fight in the first place. We mustn't forget that our end goal is love, and it is the victories we find in love that make us whole.