My Problem with Swedish Meatballs

Each time I had a Swedish meatball, I didn’t realize I was eating away at my identity.

By: POLEN LIGHT

Art by Daniel Gomes // THE UNDERGROUND

Who doesn’t like IKEA? Amazing products, environmentally conscious business, and cultural misrepresentation. On another exciting trip to IKEA with a close friend, I told him,“The Swedish meatballs are actually from Turkey.” At first, he was skeptical. Well I can’t blame him—I do occasionally say crazy shit, like to exaggerate, and have grown a reputation for being a little patriotic (I’m Turkish if you haven’t caught that). But after a quick fact-check, the information was there. The “Swedish” meatballs are actually Turkish; even the government of Sweden tweeted about it.

Photo courtesy of Twitter

What looks like a great cultural exchange story on the surface is actually a problematic story for me. Charles XII of Sweden learned the recipe when he was taking refuge in the Ottoman Empire between 1709 and 1714. He then returned to Sweden with a convoy of Turks along with the recipe for meatballs. Today, the dish is served as the famous IKEA Swedish meatballs in one of 433 locations worldwide, occasionally with a Swedish flag. You might be saying, “So what, Sweden has acknowledged the recipe was Turkish, get over it.” Personally, I couldn’t be happier that Sweden is repatriating the recipe, but IKEA still serving “Swedish” meatballs is part of a bigger problem I face.

When I meet someone new, I’m not afraid if they’re going to like me or hate me based on where I’m from; instead, I’m afraid that they won’t understand where I’m from. It’s like my hair colour is purple, but most people see it as either red or blue. This is because of identity erosion. Identity erosion happens when many small interactions undermine, degrade, or misrepresent an identity on a large scale.

When meatballs of Turkish origin are presented as “Swedish,” the Turkish identity is eroded. Identity erosion leads to more erosion as people interact and change ideas and information. With enough of these holes opening, the identity becomes unstable. It becomes a vessel for different identities rather than its own entity, and gives people the impression that the identity is open to interpretation. This leads to people filling in the gaps they’ve created.

The most common gap fillers for the Turkish identity are Middle Eastern or European. Before going on, I need to ask you a question. Do you know where Turkey is?

Photo courtesy of Wikipedia

Above you can find a world map. Unless you know where Turkey is, please take a guess.

World Map in Colour - Europe in Blue, Turkey in Red, Middle East in Yellow

Photo courtesy of Wikipedia, Edited by Author

The Turkish Republic was the successor to the Ottoman Empire, which at its height stretched as far as the North African coastline to the south, modern-day Iran to the east, and modern-day Austria to the west. The Ottoman Empire enacted several policies such as devshirme, selective taxation, and resettlement to homogenize the population, and allowed people to practice their original religion/culture.

After the national liberation war, the Turkish Republic succeeded the Ottoman Empire. The new government was founded on a similar idea; anyone who lived within the drawn borders of Turkey was considered Turkish, regardless of their heritage and beliefs, which is very similar to modern American and Canadian identities. For nearly a thousand years, the lands of Turkey served as a nexus of cultures from all three continents where they interacted and mixed with each other. Ultimately, the nexus created a melting pot for all the cultures, developing a unique and standalone “Turkish” culture.

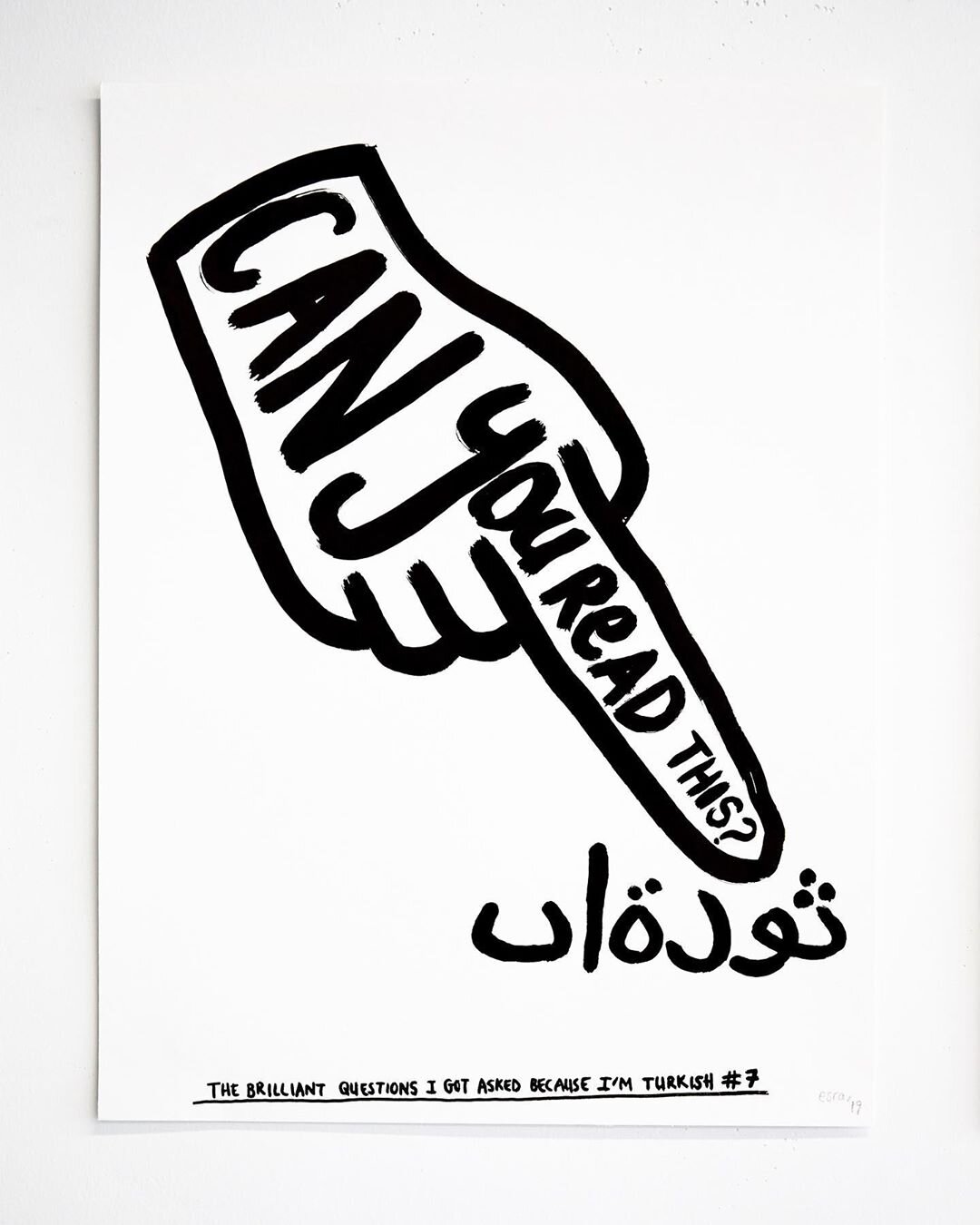

It may be argued that since the Ottoman Empire used Arabic script for their writing, it’s justified to assume the Turkish identity as Middle-Eastern. However, the Empire used a unique language known as Ottoman Turkish, mixing Farsi, Arabic, and Turkish with a complex grammar, rather than using Arabic as a standalone language. For oral communication, a form of Turkish that is very similar to modern Turkish was in use. In addition, the Turkish Republic adopted the Latin alphabet in 1928, nearly a hundred years ago, leaving little room for Middle-Eastern influence moving forward.

I lived in Turkey for 18 years, but whenever I left the country, I ran into people who had created their own version of the Turkish identity.

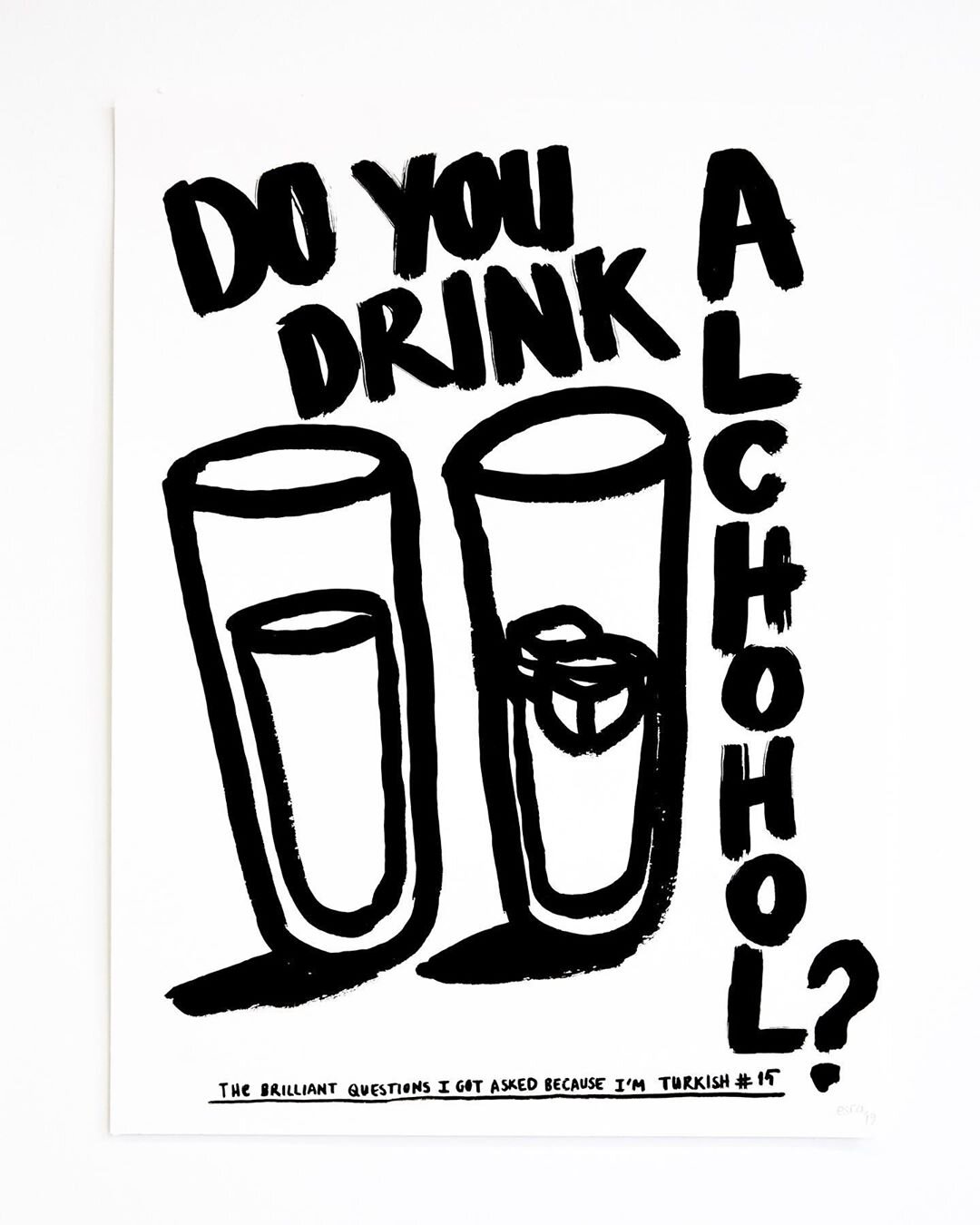

During a trip to Genoa, Italy, my group wasn’t offered alcohol initially because we were Turkish and thought to be abstaining from it. Our hosts thought they were being polite. At a science fair in Barcelona, Spain, a fellow attendee asked my friend how it was to not wear a burqa, assuming she wasn’t wearing one due to the clothing policy of the fair; this was based on nothing but the Turkish flag we had at our stand.

In my first year in Canada, during Frosh someone I met through an icebreaker activity told me that “Turks were Arabs” (which is like saying the Canadians are French). I politely corrected him. Later that year, I met someone who thought English was the dominant language in Turkey (we speak Turkish).

Earlier last year, I went out with a couple friends to a dinner where I was asked “Do you consider yourself more as European or Middle-Eastern?”. As a topic of interest, the whole table went into a debate. Strangely, nobody said Turkey was neither of those, even though we were all Turkish. Reflecting on that memory sent me down on a rabbit hole of questions, trying to come up with the root cause of people filling in the gaps themselves and why even we didn’t consider ourselves as simply Turkish back then.

To this day, I still experience identity erosion and people interpreting the cultural background of the Turkish identity in different ways. When I asked people what made them come to certain conclusions about Turkish people, the usual response was “Oh I just thought so” and “I don’t know, I guess because you’re in the Middle East/Europe.”

I realized that most people who made confident assumptions about Turkey had predesignated boxes that were based on different identities or communities. In their eyes, Turkey was either in the “Europe” box or the “Middle East” box because of historical/geographical context. When prompted to think about an aspect of Turkish identity, these people scavenged their respective boxes for a close fit to the gap, and did their best to fill it. This led me to the conclusion that the primary cause of identity erosion is indifference to said identity.

At first, it was surprising, and even funny. I would enjoy the occasional person who had a crazy idea about Turkey. How would you feel if someone said they imagined that you rode a camel to school? You would probably be amused imagining yourself like that. Then you’d correct the person and have a laugh. But what if instead of it happening once in a blue moon, it became something you began to expect? At first what I thought was a random funny interaction with a crazy guy in New York streets became my reality when they initially did not serve us alcohol in a dinner invitation “to be polite.” Then I started paying attention, and it was everywhere—the hotel clerk, the auntie riding next to me on the bus, and eventually, every other person.

Every time I say I am from Turkey, I wonder what they think of me. It would be absurd to say “So what do you think of Turkey?” or “What do you know about Turkey?”. They might have the craziest idea or the most innocent and neutral perspective, but regardless it would be rude and inappropriate to ask. So I live with constant puzzlement, thinking if they see me as I am or someone with a far from true background.

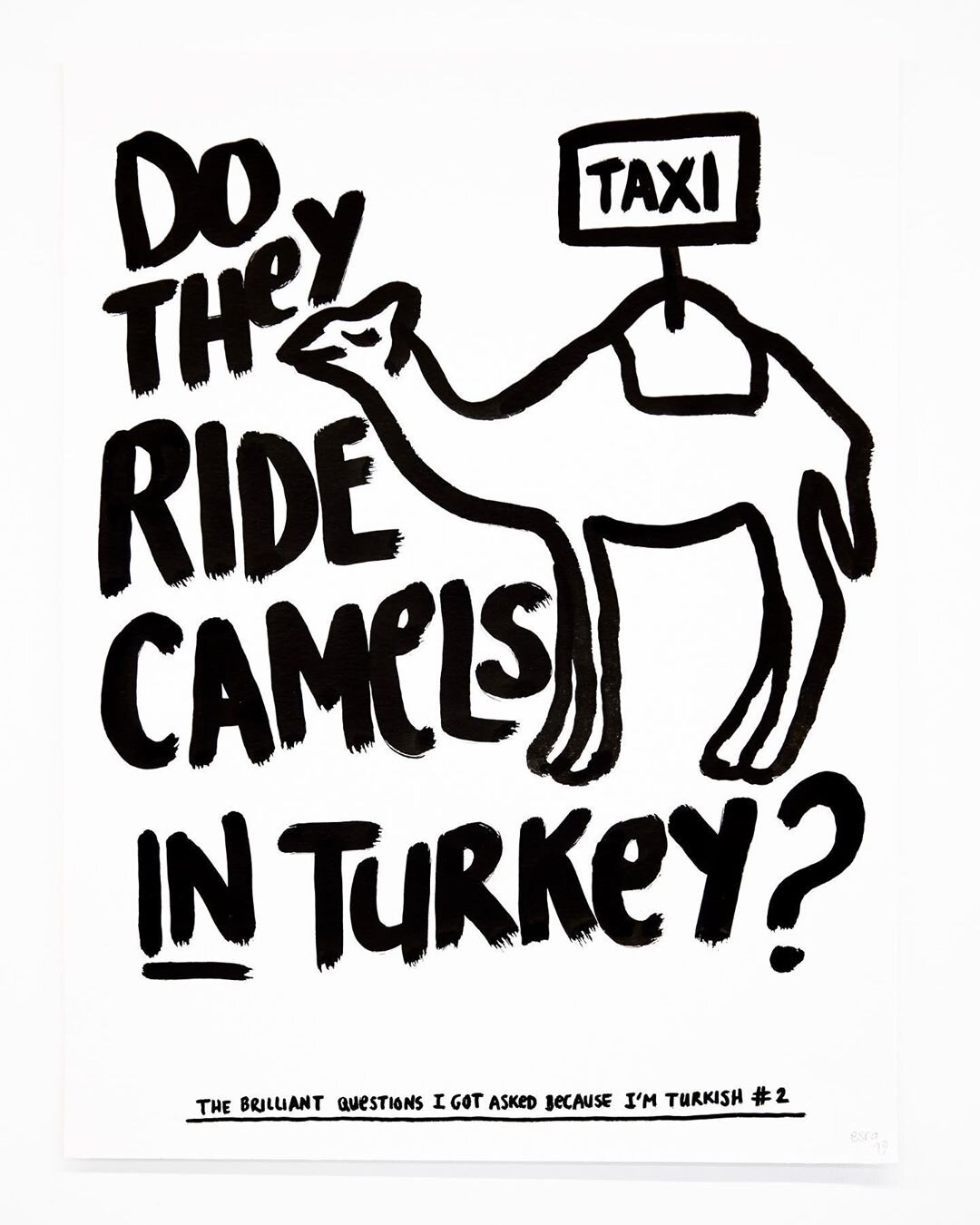

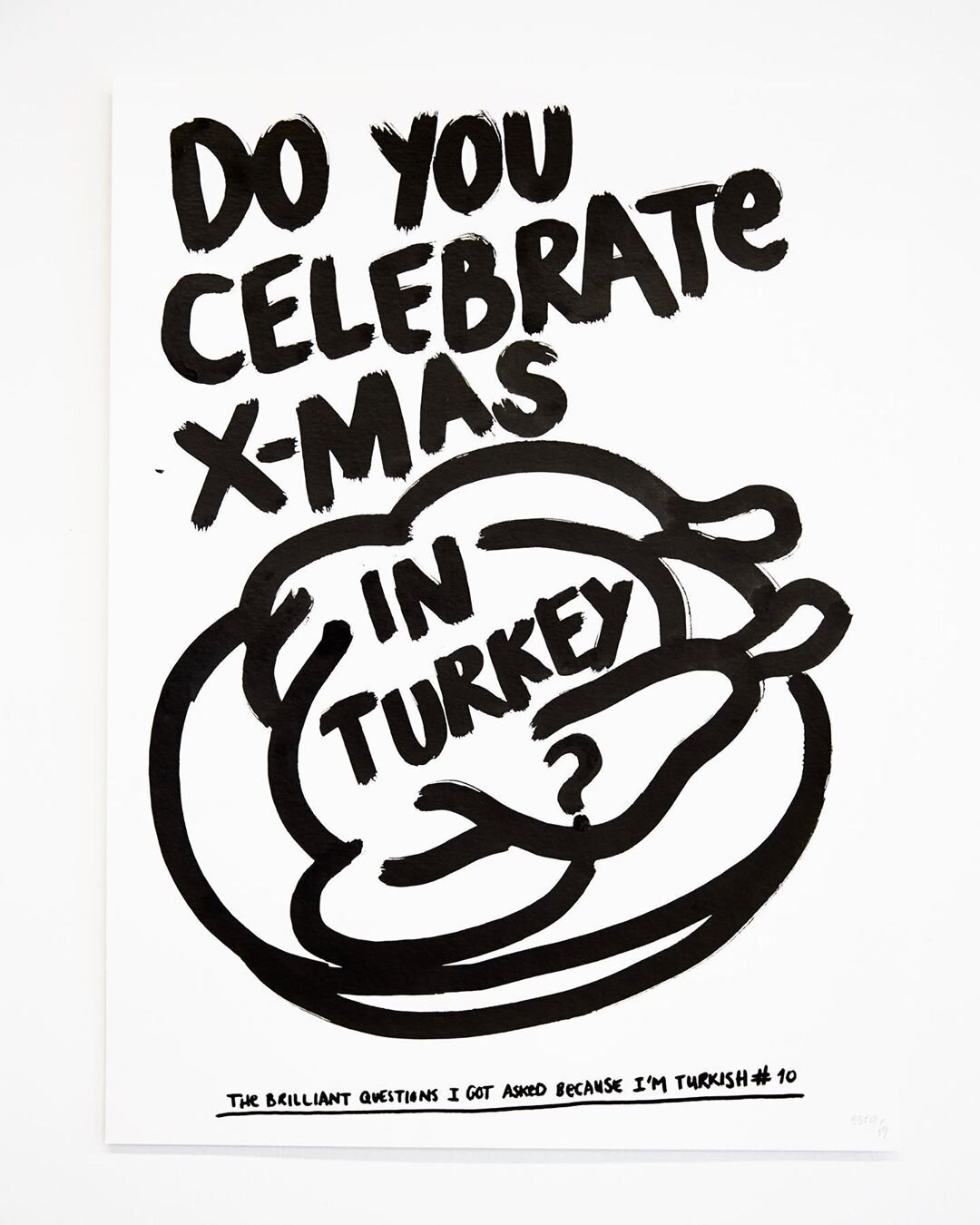

Artist Esra Gülmen explores this in her 2019 exhibition Don’t I Look Turkish in Berlin. The photo series reflects questions Esra received because she expressed she was Turkish.

Pieces from Esra Gülmen’s 2019 exhibition Don’t I Look Turkish in Berlin. Photos courtesy of Esra Gülmen. Other images from exhibition: 1 2]

Esra’s pictures are actually fun depictions of a frustrating reality. It’s like two people are making small talk and one of them finds out the other is a doctor. Then they start telling the doctor about a bad ache they have and ask for an opinion. That doctor probably doesn’t specialize in aches, and even if they did, small talk isn’t really a good idea to get medical advice. And what of the doctor? They were having a nice conversation until the person asked unreasonable questions merely because they mentioned they were a doctor.

That’s what it feels like getting those questions. Once I mention that I’m from Turkey, the personality I had during the previous interactions evaporates and is consequently replaced by a camel rider, maybe an exotic person. The conversation then becomes me trying to politely correct the person, derailing the flow of the conversation, and creating a small tension; in most cases, it becomes a negative interaction.

With each negative interaction that reduced my identity to a pre-existing box or stereotype, I was more confused about who I was and what my culture stood for. My identity eroded, chipping away little by little, until eventually I started disliking it. As a consequence, I tried to cut ties with the identity I cultivated for myself. I hid my Turkish identity. When I saw Turkish people in a foreign country, I spoke to them in English. When I went to a Turkish restaurant, I asked my companions not to mention I’m Turkish. In my early years in high school, one of the primary reasons I chose to study abroad was to also leave Turkey behind.

After coming to Canada, I had the perfect opportunity and environment to let go of my Turkish identity. I didn’t have to partake in Turkish cultural interactions and I didn’t have to deal with Turkish problems.Yet something was not fitting right; the grass wasn’t greener on the other side. The identity I wanted to let go of was actually really fitting, and the only reason I wanted to let it go in the first place was the erosion. I then realized this was a vicious cycle: because it was eroded, the Turkish people weren’t able to connect with it.

After embracing my identity even more deeply than before, there was a new challenge waiting for me. I accepted my identity not as a vessel for other ones, but as a unique identity formed by the blending of many others. While most assumptions come from pure, unmalicious ignorance, there are people who remain indifferent to the idea of reparation and need to be told the other side of the story. I can’t go back to my debate a year ago and remind my fellow Turkish friends that we are simply Turkish, but starting now, we have to share our part of the story with the world.

The condition of an unstable cultural identity isn’t unique to me; unfortunately, many of us suffer the same regardless of what culture or background we come from. I have Turkish friends who consider us to be part of another group. I know people of Turkish origin who left their identities behind to adopt another. I’ve also met many others who left their cultural identities for another. Each time someone completely abandons an identity or experiences erosion, the identity vanishes little by little.

While I hope I haven’t taken away your desire to eat IKEA meatballs (because they are damn good), the reality has not changed. Acknowledging “Swedish” meatballs as Turkish is more than a matter of national pride. Not giving one identity enough significance to view it independently of others undermines it when carried out on a large scale and ultimately chips away from the culture and identity of the undermined.

Recognizing “Swedish” meatballs as Turkish or Istanbul as the original tulip capital, is the primary action that needs to be taken; giving significance to and not categorizing individual identities, as well as favouring reparation, is the attitude that needs to be embraced. What some may consider as little are what identities are built and thrive upon. It is what makes us connect as a community, and allows us to contribute to the world.

Photo courtesy of Twitter

So next time you’re in doubt about an identity, don’t fill in the blank or make assumptions. Instead, ask someone in that community for their opinion and ideas. Trust me, if there is anything I like more than eating sarma, it is talking about and educating people on my culture.