The Party to End All Parties: Celebrating the Apocalypse in Film

Welcome to the end of the world. We have a DJ and an open bar.

In the 100 years since T.S. Eliot wrote that the world would end “not with a bang but a whimper,” our doomsday-themed films and books have proposed another option: the world will end with a massive rager. With no way to avert the apocalypse, humanity throws a party instead. It’s like the biggest New Year’s Eve celebration ever, with music, food, drugs of all kinds and the people we love. Near midnight everyone counts down to their extinction. Champagne is popped. Annihilation is certain. You might as well drink too much and dance sloppily to Doja Cat.

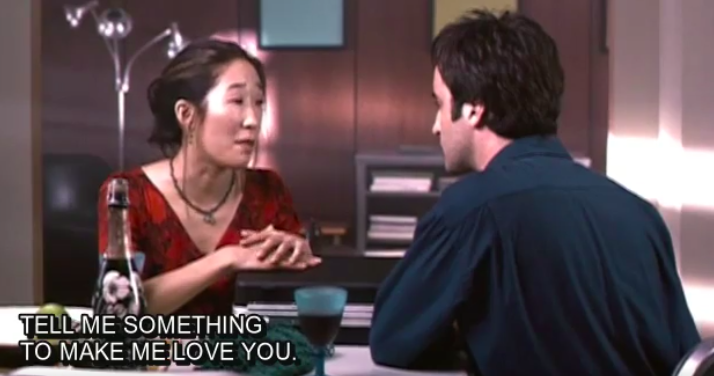

Torontonians party till the end in Last Night (1998) // Photo via Deeper Into Movies

In an age of climate catastrophe, violent conflict and viruses that bring the world to a standstill, it’s only natural that doomsday stories catch our attention. They allow us to visualize the end safely and our role in it, acting as a sort of sandbox for armageddon. We may imagine ourselves as heroes, braving fire and brimstone to save our family or even the whole world. But while there is an abundance of these action-packed disaster blockbusters, other narratives take what is perhaps a more realistic approach. Were the world indeed coming to an end, most of us would not spend our final days battling zombie hordes or leaping over gaping sinkholes. Instead, we would probably spend time with our loved ones, pursue a hobby, and of course, throw the wildest parties ever.

Therein lies a major distinction between the apocalypse in these disaster stories—in which a few plucky heroes fight to survive the end—and the simpler, more inevitable doomsday. If disaster media gives us hope for humanity’s survival, the apocalypse party narratives show us the silver lining in our imminent end. Knowing they won’t live long, the characters decide to live well. They can free themselves of unsatisfying jobs and stifling relationships, replacing the humdrum routine and inhibitions of everyday life with everything they really want to do.

Three weeks before the world ends, street flyers get interesting in Seeking a Friend for the End of the World (2012) // Photo via Movie Screenshots

It’s a simple yet revealing question: what would you do if you knew it was your last day on Earth? And the natural follow-up would be, what is keeping you from doing that now? Put simply, the apocalypse offers us the opportunity to do whatever we want, with practically no consequences to worry about.

This license for debauchery characterizes a final dinner party in Seeking A Friend for the End of the World (2012), as an imminent asteroid collision sees humanity waiting to be wiped out. The party guests have embraced hedonism fully, decked out in the jewels they were saving for a special occasion while their children drink cocktails in the background. One man drunkenly brags about having been with a different girl every night since the apocalypse was confirmed. The asteroid has made it easier to land sexual partners, he claims, because they don’t care about diseases, if you call them back, or if you can provide for them. Two guests arrive, having scored heroin, and the others clamour for a hit. It may seem irresponsible, but concerns for health and societal standards probably feel insignificant in the face of certain death. There is the suggestion that people are fundamentally curious about all the ‘bad’ behaviour we’ve been told to avoid. With only two weeks before the planet is turned into an uninhabited wasteland, we can let our curiosity and hunger for pleasure win. If there ever were a time for trying hard drugs or fulfilling weird sexual fantasies, that would be it.

Maybe this whole impending-extinction thing isn’t so bad // Photo via IMDb

It’s also no surprise that mind-altering substances and sex are staples of the apocalyptic genre. Many of us would find the end of the world difficult to cope with and would turn to the nearest source of comfort to block out the approach of the asteroid or the deadly plague. For those of us who spent the COVID-19 lockdown drinking wine from the bottle, sleeping till noon and mindlessly bingeing reality television, the value of effective distraction is not to be understated. In films, too, characters turn to various forms of escapism in their final hours on Earth. A local diner becomes the site of a drug-fuelled orgy for staff and customers alike in Seeking A Friend for the End of the World, while another impending asteroid impact in Don’t Look Up (2021) leads two characters to simply “get drunk and talk shit about people.” Cocktails, sex and gossip: the perfect way to ring in the end of civilization.

Pre-gaming before Armageddon in Don’t Look Up // Photo via Netflix

The apocalyptic party doesn’t have to be a debauched rave, though. In Silent Night (2021), a global environmental catastrophe doesn’t stop a group of old school friends from gathering for their annual Christmas party, complete with resurfacing tensions, snarky comments and other petty drama. The signs of the end are everywhere: in the storm brewing outside, the designer heels one character bought with a now-useless university fund, and the government-issued suicide pills the friends have decided to take after midnight. Knowing that this is their last night on Earth, the characters have made this Christmas party special. The children are allowed to swear, everyone is dressed to the nines, and sticky toffee pudding must be on the menu, even if the fathers have to break into a Tesco to acquire it. As the evening progresses, the friends reveal secret jealousies and affairs, gossip about other people and, even in their silliest moments, take comfort in the fact that none of this will matter in a few hours.

Everyone may be about to die, but the festive spirit is very much alive in Silent Night // Photo via IMDb

However ridiculous the characters may seem at times, the film is about friends and family sharing one final night of enjoyment before the end. This, too, is a common element of the inevitable, unsurvivable apocalypse. In Don’t Look Up, the characters spend their very last moments laughing and chatting over dinner, holding hands as the walls begin to shake. Perhaps this is how most of us would want to head into the apocalypse—surrounded by our loved ones, celebrating the lives we have led and the people with whom we shared them.

The last supper in Don’t Look Up // Photo via IMDb

Of course, this may not be possible for everyone. In Seeking A Friend for the End of the World, Penny finds herself stuck in the United States after commercial airlines have ceased operations. Having just broken up with her jerk boyfriend, Penny realizes she wasted time she could have spent with her family in England. With only two weeks to the apocalypse and no way to get across the Atlantic, she is too late to reach them. This heartbreaking scenario was the reality of many international students and immigrants living away from their families when the pandemic hit and continues to be so for those with loved ones in conflict zones with escalating violence. Most of us say we would like to spend our last days with our loved ones, but what happens if they are on a different continent when the end comes?

Maybe the destruction of the world can push us to make new connections before we’re wiped from existence. Even as she laments the time she wasted on her failed relationship, Penny finds friendship—and love—in the lonely but kind neighbour to whom she had never spoken before. Another film brings the apocalypse right here, to Toronto. In Last Night (1998), Patrick (played by director and U of T alum Don McKellar) and Sandra begin their last evening on Earth as strangers when he agrees to help her locate her husband, but they form a profound bond that culminates in a perfectly satisfying ending. While Patrick attends a mock Christmas dinner hosted by his parents, he spends it clashing with his sister’s boyfriend and upsetting his mother with his refusal to stay until the end of the world at midnight. He intends to die alone but finds genuine comfort in Sandra’s company, and the two have their own small celebration with cheap wine and folk records. Even if our friends and family are distant from us, whether physically or emotionally, maybe there are others around us who seek a friend for the end of the world (or for something that feels like it, anyway). These stories are a testament to the power of some relationships, however short-lived, to provide solace and meaning amid catastrophe. As Sandra tells Patrick, “There is something to be said for human companionship.”

With hours to go before the apocalypse, strangers Sandra and Patrick build a connection // Photo via Criterion

When doomsday arrives, most of us won’t die in a particularly heroic or remarkable way. Whether we spend our final days letting loose at a rave, reminiscing with friends and family at dinner parties or getting to know someone new who fills us with wonder and laughter, we will celebrate life in the face of extinction. Maybe we’ll finally be able to live the way we wanted and realize the beauty of this world as it ends—not with a bang, perhaps, but certainly not with a whimper.