Youth, Interrupted: What Wartime Literature Says About Disillusionment Amidst Global Catastrophe

The First World War transformed the just-begun lives of a generation of adolescents. Over a century later, the art they created resonates with another group of young people facing extraordinary loss and uncertainty.

BY: TANISHA AGARWAL

As part of the World War One unit in my eighth grade history class, our teacher made us watch All Quiet on the Western Front, the 1930 film adaptation of Erich Maria Remarque’s classic novel about a group of young German soldiers experiencing the misery and horrors of life in the trenches. I had many questions as I watched, such as, was it almost lunchtime yet? Why are old-timey movies so long? Was the lead actor actually attractive, or was I just bored? And why did we have to watch this? Couldn’t we just read a few pages on tanks and the Somme and call it a day?

To his credit, my teacher often emphazised the youth of the soldiers, who were “not much older than you all,” he’d say. But between memorising dates and doing presentations on battle tactics, it was hard to feel any connection to these people—when we thought of them as individuals at all, rather than a formless mass contained within the unfathomable numbers in our books. Rationally, we knew that the war destroyed places, families, and lives. We knew, thanks to our textbooks, that it resulted in 21 million deaths. We knew that it was one of the greatest tragedies in history, but it was exactly that—history. There was no way we could understand what it was like to live through a worldwide crisis that upends daily lives in such a profound manner, with no clear end in sight and virtually no hope of ever going back to normal.

You probably know where this is going.

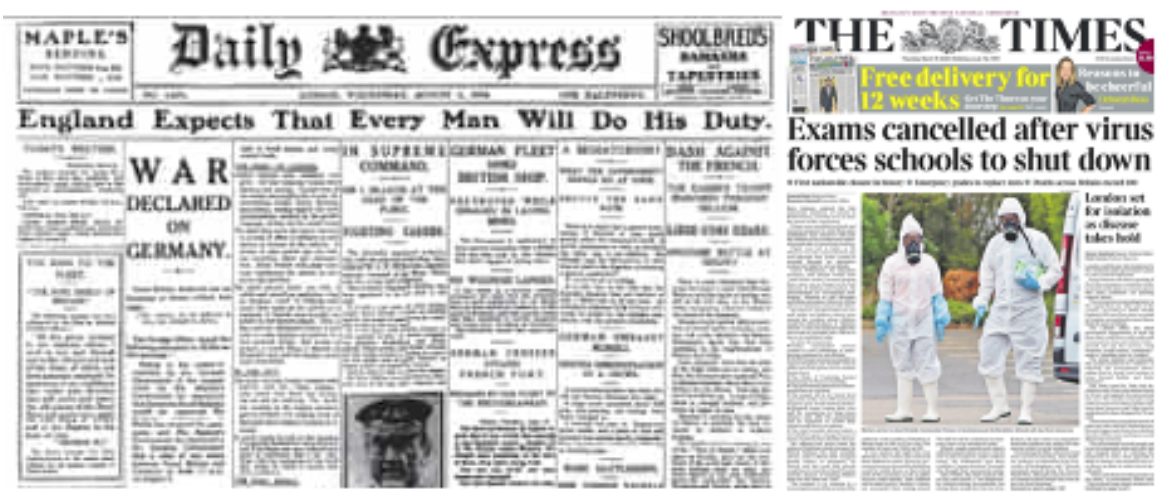

Headlines from August 5, 1914 and March 19, 2020 / Photos courtesy of The Daily Express and The Times via Twitter

Along came COVID-19 to fix that problem for us. Since the beginning of the pandemic, we have heard its death toll compared to casualties from World War One and the disease itself likened to the Spanish influenza outbreak that followed soon after. But perhaps a less obvious similarity is in the transformative effect of both the pandemic and the war on daily lives, particularly those of young people who are just beginning to find their own way in the world. They are the people who are old enough to comprehend the dire nature of the situation but too young to have already attained the financial and emotional stability needed to tide them over during the crisis. As if making decisions about and planning for their future isn’t stressful enough, every expectation and cautious hope for that future is demolished by factors completely outside their control.

Like many others, I decided to spice up my lockdown routine and avoid losing my mind by learning something new. I started on Khan Academy’s 20th century playlist to refresh what little I remembered from high school. This time, however, I supplemented the facts and dates with what I was really interested in—the people of the war. Not kings and kaisers, but the ordinary soldiers, civilians, and non-combatants whose stories I wanted to hear in their own words. I read about the World War One poets and became hooked. Their hopelessness and frustration mirrored my own state of mind. The same grief that felt so incomprehensible five years ago now hit so close to home that I had to intersperse my reading with video games and sitcoms to keep from drowning in my own worst emotions. At the same time, it comforted me like nothing else. As I drifted from my friends and irritably clashed with my family, the knowledge that someone had felt a similar fear and despair about their future meant everything.

Epigraph of All Quiet on the Western Front, translated by Brian Murdoch for Penguin Vintage Classics

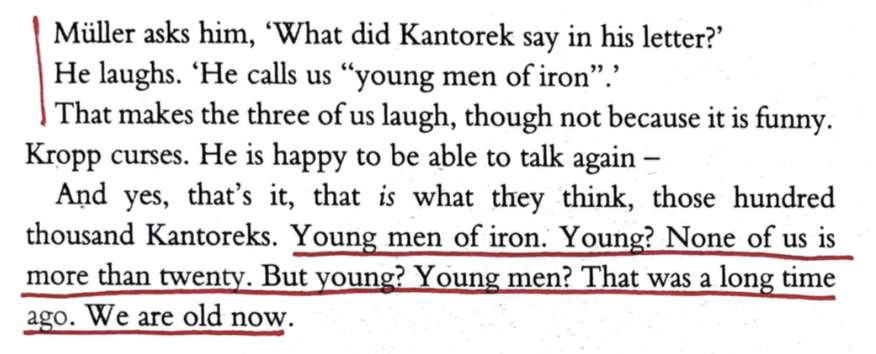

It was at this time that I read Remarque’s All Quiet On The Western Front. Originally published in German as Im Westen nichts Neues, it was based on the author’s own combat experience and was banned in Nazi Germany for its unvarnished portrayal of the war, which was at odds with the government’s militaristic propaganda. The book can be finished in a single sitting, being only 200 pages of extraordinarily captivating writing. It took me a little longer to read it, mostly because I kept stopping to underline passages and draw exclamation points in the margins. The horrors of the artillery shelling and gas weapons are described with remarkable eloquence, but it was the characters that stood out to me—their disillusionment, anger, and the detachment they feel from the carefree teenagers they used to be.

They express the same concern that haunts Generation Z about their futures, distinguishing between the older soldiers who will return to their former jobs and lives and the children who will not bear the scars of a war they can’t remember. Trapped in the middle are the young adults, those who never had the opportunity to build their own identity before the war handed them one. “We had just begun to love the world and love being in it;” says the narrator, “but we had to shoot at it.” It is the all-too-familiar tragedy of a generation coming of age amidst catastrophe.

People often say COVID-19 put life on pause, which I think is a misleading phrase. It suggests that a return to the ‘old’ world is possible as soon as we push play. But with the pandemic still going strong after more than a year and a half, its impacts may prove similarly enduring. Already, remote technology is being heralded as the future of education and work. More worryingly, disparities in technological access and know-how coupled with financial concerns threaten to leave many young people behind as learning has shifted online and family incomes have been slashed. This is to say nothing of the immense damage to adolescent mental health from the effects of lockdowns and Zoom classes. Remarque acknowledged the long-term impacts of WWI, particularly the alienation and emotional struggles of the veterans as they reintegrate into civilian life, in The Road Back, a sequel-of-sorts to All Quiet. It highlights how young lives aren’t just temporarily disrupted by crisis, but become defined by it. It’s the equivalent of pressing the play button to find that the video is suddenly, unmistakably distorted.

None of this is to say our troubles are the same as theirs. I know that quarantine and online school is a far cry from the gruesomeness of trench warfare. But too often, older generations are quick to dismiss teenagers and young adults’ struggles in the pandemic as oversensitivity, citing the youth of WWI as the pinnacle of self-sacrifice and courage. “Those kids didn’t whine or run from suffering,” says the generation that has been in neither our shoes nor theirs. But to anyone who actually reads the literature that came from the trenches, military hospitals, and grieving homes, this argument is comical in its lack of self-awareness.

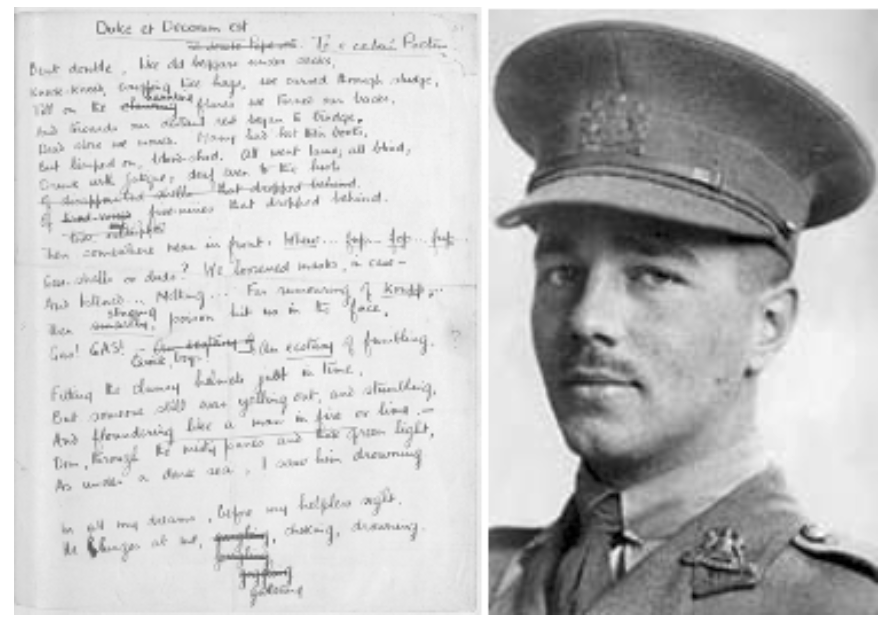

Like Remarque’s novel, many of the literary works of this period are grim and despairing in their portrayal of lost innocence and senseless violence. Among the most famous of these, known to English literature students everywhere, is Wilfred Owen’s “Dulce et Decorum Est”, a staunchly anti-war poem that criticises in particular the glorification of battle by older generations. The horrific description of the effects of mustard gas betrays the truth about the anger and disenchantment at the front. Owen himself enlisted in the British Army at age 22 and was killed in action three years later, only a week before the Armistice was signed. Most of his poetry was published posthumously with help from close friends.

The original manuscript of “Dulce et Decorum Est”, written while Owen was being treated for shell-shock at Craiglockhart Hospital in 1917 / Photos via The British Library and BBC

One such friend and fellow soldier-poet, Siegfried Sassoon, famously penned a letter of dissent to his commanding officer which was then read aloud in Parliament. In the statement, Sassoon, a highly-decorated infantryman who had received the Military Cross only a year prior, refused to fight “for ends which I believe to be evil and unjust.” On the home front, Vera Brittain’s memoir Testament of Youth details her grief at losing her brother, fiancé, and friends in the same war, prompting her to become a leading pacifist thinker. Even John McCrae, the Canadian doctor—and U of T alumnus—whose iconic and somewhat romanticised poem “In Flanders Fields” was used to recruit soldiers into the army, took a more cynical view of the war several years later in his final poem, which looked ahead to an eventual end of the war when the fallen servicemen would finally be able to rest in peace. Were they alive today, I don’t think these men and women would appreciate the effort to glorify their suffering as courageous or noble.

Vera and Edward Brittain in 1915, three years before Edward’s death at age 22 / Photo via Spartacus Educational

There is a different, more helpful way of approaching this comparison. The continued relevance and popularity of these works speaks to the power of literature to help us feel less alone in anxious and uncertain times. We understand the anxiety and sadness that the wartime writers felt because at some level, we feel the same, albeit in a very different time. As is so often the case, humans turn to art to make sense of what is too awful to share otherwise. The outbreak of COVID-19 saw an uptick in sales of pandemic-related fiction such as Emily St John Mandel’s Station Eleven, a novel that spotlights the loss of everyday pleasures like music, theatre, and sports in a post-apocalyptic world where most people are preoccupied with simply surviving the day. Within a few months of lockdown, young people were already creating art to express their emotions, dark as they may be, to make sense of the mental impacts of isolation and sudden unpredictability of their futures. From poetry written in Zoom classes to an entire EP penned by fans on a singer’s Instagram over two days, young people are channelling their frustration and anxiety into media they then share, letting others know they are not alone in navigating this bizarre new world.

Arrested Youth wrote his lockdown-themed EP in collaboration with fans in an Instagram Live / Photo courtesy of Arrested Youth via Spotify

With all its beginnings, endings, and uncertainty, the hazy period between youth and adulthood has always been uniquely challenging. Crises like wars and pandemics combine with the existing emotional turmoil to become not just life-changing but generation-defining. But with the anger and pain comes poetry and art that endure long after those terrible events have been reduced to facts in a history textbook. The writers of WWI found solace, or an outlet for their frustration, or both in creating art. Over a century later, their work is a source of comfort to young people finding their own way through troubled times. At the same time, it’s an inspiration to generate creativity from emotional chaos—and in doing so, perhaps see a future generation of youth through another unprecedented catastrophe.