Demystifying Arranged Marriages for the Digital Diaspora

“IS THIS A DATE OR AN INTERVIEW?” A guide to this long standing practice for my fellow American-Born Confused Desis (ABCDs)

BY: VAISHNAVY PUVIPALAN

Ram Rajyabhishek by Raja Ravi Varma / Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

On Indian Matchmaking

Indian Matchmaking premiered this summer to mixed reception and suffice it to say I was more than a little surprised. As it stands, it retains a meager 63% score on Rotten Tomatoes’ Tomatometer. In summary, the eight-part series by Academy Award-winning filmmaker, Smriti Mundhra, documents the process of the longstanding Indian tradition of arranging marriages. It follows seasoned marriage broker, Sima Taparia, also known as Sima “Aunty,” a no-nonsense-Indian-fairy-godmother type. She takes on the task of bringing love into the lives of six eligible singles of Indian descent residing in the US or mainland India, always with her one true maxim for holy matrimony: adjustment and compromise.

Pictured (from top to bottom): Aparna Shewakaramini, Pradhyuman Maloo, Shekar Jayaraman, Nadia Jagessar, Sima Taparia / Photo via Netflix

I thoroughly enjoyed the show and appreciated all the in-jokes the way only a South Asian could. Sure, the line between semi-educational documentary and reality TV was blurred at times but that was all part of the fun. And I was happy to see some faithful representation in western media, you know, something other than the token Bollywood Nerd. However, a quick scan of critic and audience reviews indicated to me that many took issue with the show’s integrity when it comes to depicting the reality of Hindu arranged marriages. The criticisms are mainly concerned with its unwillingness to engage with the misogynist, classist, casteist, colourist (just about every problematic ‘-ist’) views that are so casually purveyed throughout by much of its colourful cast.

Yikes. / Photos via Netflix

I was a little guilty that I hadn’t been more attuned to these glaring offences. I myself am a first-generation Sri Lankan immigrant, shouldn’t I partake in the outrage? The issues at hand I know are rampant in this community, mainland (and to a lesser but still significant effect) diasporic alike.

The ABCDs of The Cultural Divide

I think my lack of sensitivity stems from the distance I perceive between myself and the Hindu community. There’s a sense of “I’m brown but I’m not that brown, therefore I can’t relate and therefore it isn’t my problem.” And this is despite the fact that nearly every marriage in the expanse that is my family was arranged. I’m not alone in this sentiment either. This sort of detachment is common for American-Born Confused Desis (ABCDs). The term is sometimes used by mainland South Asians and immigrant parents to denigrate later generations for being removed from their roots, “white-washed,” if you will. It is also used as a self-identifier by those living in diaspora who also have difficulty reconciling the Western and Desi aspects of their identities --people like myself.

De·si

/ˈdāsē/

INDIAN

noun

a person of South Asian descent who lives abroad.

In any case, the more I think about my fated marriage and all the arranging that will go behind it, the more motivated I feel to better understand this part of my history. How far has this centuries-old tradition come along in the modern day?

A Brief Overview of Centuries-Old Tradition

First things first, I should clarify that, today, an arranged marriage is defined as a marriage facilitated by the bride and groom’s families. It’s like a normal wedding but your parents pre-approve of your partner first. It has been practiced in some form in every continent, but for the purposes of this article I will be looking at Desi arranged marriages, more specifically, of the Hindu variety.

“The Marriage Settlement” is the first of a series of paintings by 18th century English painter William Hogarth entitled Marriage A-la-Mode satirizing arranged marriages / Photo via Wikimedia Commons

There is an important distinction to be made between arranged marriages and forced marriages. A forced marriage is conducted without the consent of the parties to be wed while an arranged marriage takes place only with the consent of both the bride and groom.

Hindu arranged marriages have taken place since as early as 200 BCE to 200 CE as outlined in the earliest Indian legal text, the Manusmriti.

“Decking the Bride” by Raja Ravi Varma in 1893 / Photo via Google Arts & Culture

They are endogamous, meaning the expectation is to marry within one’s social stratum, ethnic group, and caste. In fact the system was primarily created to maintain the upper castes. Secondarily, it is a way to maintain wealth. The process also takes into consideration astrological compatibility.

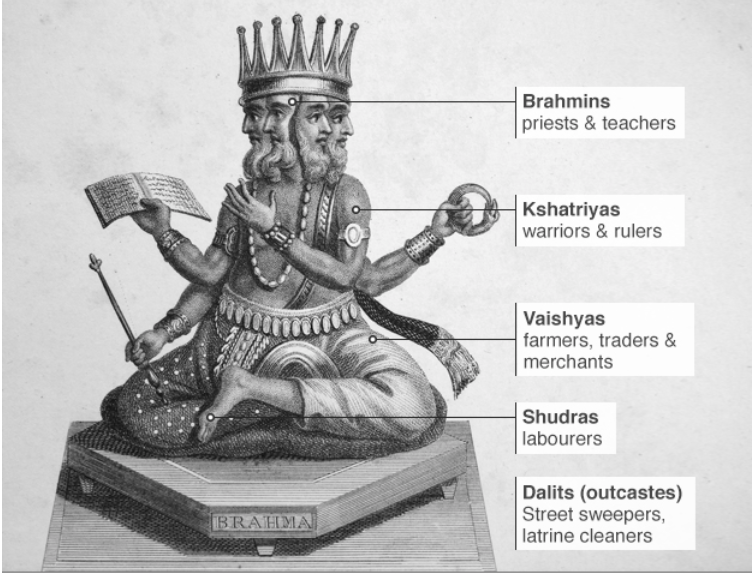

The Hindu deity, Lord Brahma, God of Wisdom, is used to illustrate the hierarchy of the caste system / Photo via BBC

The caste system is a socially enforced hierarchy based on occupation. Caste discrimination remains a deeply rooted problem in India today.

I think the fact that South Asian cultures still hold onto this tradition is reflective of their more collectivist values in contrast to the West’s fixation on individualism. Having anyone besides yourself involved in your marital status doesn’t sit well out here because so many value their independence over a sense of community. This isn’t at all the case for Hindu society where the credo is “you’re not marrying a person, you’re marrying a family.” And how, inn Hindu joint families, you never leave the nest; generations after generations share the same roof.

Modern Matchmaking

Now, equipped with a rudimentary understanding of the history of Hindu arranged marriages and the values that inform them, I wanted to see how the whole process has been updated. It turns out I have three options. For one, I could go the old-fashioned route. My family might look into its vast network and pray that they might find someone who knows a guy who knows a guy who just so happens to be of marrying age. This might work. But, I would have to keep in mind that should it not work out, it could be amicable or it could trigger something of a decades-long feud.

I could also go the marriage bureau route. Marriage bureaus are companies which employ matchmakers like Sima Aunty. They have access to the “biodata” of a host of bachelors and bacheloresses looking to settle down. Biodata sounds a lot more sci-fi than it actually is; it’s just a portmanteau of biography and data. The term is used interchangeably with both resume and matrimonial profile and for good reason:

Exhibit A: The Competition (sample biodata) / Photo via Zety.com

The prospect of condensing my life’s achievements, physical appearance, family history, and romantic expectations to a single page and printing it off for review at the hands of who-knows how-many suitors is daunting -- and the prospect of rifling through and comparing resumes as my parents and a matchmaker standing by to find “the one” is even more so. I think a more automated process would suit my anxious tendencies. Which brings me to my third option:

Digital Matrimonials

With the advent of the internet, the matchmaker was not made obsolete but instead it took on a different form, dating sites. Shaadi.com, founded in 1997 predates its most popular western counterpart, OkCupid by seven years. Shaadi.com, along with Jeevansathi.com and BharatMatrimony take the arranged marriage tradition to the web. At surface, these sites look like any other dating site --your eHarmonys and Christian Mingles-- but in my adventure in digital marriage arranging on Shaadi.com, I spotted some key differences.

Screenshots via Shaadi.com

When I went to register for the site, I was greeted by the sign-up form above. Pretty standard stuff, e-mail address, password, gender, and… who’s setting up this profile. That may seem a little odd but it makes sense that a culture where weddings are a family affair would be reflected in its dating platforms.

The next steps of the registration process also revealed some core values in arranged marriages that persist today.

Screenshots via Shaadi.com

At the forefront of required fields are ‘religion’ and ‘community’ (referring to ethno-linguistic groups, e.g. Tamils, Gujaratis) and just after that is whether or not you reside with your family. I anticipated this as family values, faith, and ethnicity are integral for compatibility in Desi communities. I was also asked about my education, career, and income as well as my height and diet (I was tickled by ‘eggetarian’), more information one would typically include on a dating profile. But a little more problematic is the inclusion of ‘sub-community’ as a required field. In this context, sub-community euphemistically refers to caste.

Upon entering the site as a member and doing some research, I found some more instances of regressive values embedded in the site.

For one, just this summer, a skin complexion filter was removed from the site’s algorithm thanks to the work of three South Asian women inspired by the BLM movement, spearheaded by Meghan Nagpal, a Toronto user of the site. This sort of reverence for lighter skin is a hot button issue in India and adjacent countries. Also this summer, the infamous Fair & Lovely, a skin lightening product and giant in the Indian beauty industry, was rebranded to Glow & Lovely.

There. Problem solved. / Photo via Unilever

That aside, I also found it troubling that users on Shaadi.com cannot connect with members of the same sex. Though this is something I anticipated, considering the conservative foothold in Desi cultures and because Shaadi.com is older among other matrimonial sites.

But you would expect a flashy new dating app that purports to be a Tinder for South Asians to be different, right? More accessible for the LGBTQIA+ community?

Nope. Three years later and no such feature has been implemented ♡ / Photo via Dil Mil on Facebook

So, yes. There’s a lot still wrong with the arranged marriage process online and otherwise. And while small strides toward more progressive values are underway owing to the work of dedicated activists, there is much room for improvement.

The Takeaway

While I could spend all the time in the world analyzing the mechanics behind arranging marriages and their implications, I would be remiss if I didn’t consider the results. What if this (some might consider needless) endogamy still persists because it’s so effective? The answer to that is not easily found. Up to sixty percent of the world’s marriages are arranged and they maintain only a five to seven percent divorce rate. But I’m not so sure about using lack of divorce as the sole indicator of a successful marriage. Also, it is my hope that because so many marriages are arranged, that there will be a serious overhaul of the values that the process perpetuates.

On the one hand, I’m surrounded by testimonials from my family and community; one half of a couple very close to me would tell me, quite mirthfully, “I met my husband for the first time at the altar. We’ve been married for twenty years.” On the other hand, to bring it back home, none of the couples on Indian Matchmaking ended up staying together.

While I’ve certainly learned a lot about my history I can’t definitively say I’ve learned anything about my future. The jury’s still out on whether first comes marriage and then comes love.