A Field Guide to Allyship

“How can I be an ally?” and other impossible to answer questions.

BY: NOAH FARBERMAN

Art by Noah Mackenzie

I’m new to this, I want that to be clear. New to more in-depth writing, but I am also new to sharing anything personal or serious. I am young, in my early twenties. I live with my family in Lytton Park, where I spent the latter half of my childhood. I’m straight and white, with the pronouns he/him. But sometimes I’ll say my pronouns are “he and hey! What’s up” if I think the crowd is down for it.

But you’re not here for jokes, you’re either here because you want to learn about allyship or you are here for jokes and this is an awkward disappointment.

This is all going to be filtered through me, your early twenties, straight and white-guilty, comedian tour guide. But before we start down the road of sharing I want to remind everyone sitting in the ally section of the boat (it’s a metaphorical boat tour down the Danube, that’s not pertinent but I really need my metaphors to be clear) that this isn’t about you. It’s not about me, either.

Quickly, what is allyship? Simply put, allyship is the process of being supportive to a group (often a marginalized one) that you're not a part of. To better understand what allyship can look like in practical terms, I reached out to three people with different backgrounds and asked them each the same question: If someone were to approach you earnestly on the street and ask “how do I be an ally?” how do you think you would respond?

Before we go any further I want to make my point clear. These people that I spoke to aren’t group representatives or world leaders (yet, who knows), they are just my friends. The point of these interviews is not to compile a list of answers. Everyone is going to have a different answer because everyone’s interpretation of allyship, or respect in general, will always be different.

So, who did I, your self-proclaimed humble tour guide, ask for advice on how to be a better ally? I asked my friend Sean. Sean is a little bit older than me. We had a similar post-secondary education. He’s very well-read and just as well written. He’s a good friend, smart, someone whose opinion I can always trust even when we disagree. Sean is also straight and white.

Sean’s answer was concise and effective. “Speak when it’s hard. Listen when it’s easy.” What does that mean? Does it mean hijacking the microphone at Crews and Tangos to let everyone know that you support them? Hard no. Don’t do that. Respect the stage, always. As Sean and I continued to talk it became clear that the base intent behind those words was being an ally doesn’t end when you’re not with your queer friends. According to Sean, being an ally isn’t standing up for someone in front of them, being an ally is standing up for someone when they aren’t around.

I understood this as, when you’re standing with a group of guys and one of them says “nah man, I am not going to the marina, that place is gay,” you can’t laugh or play along to avoid causing a scene in front of friends. You, the bystander, need to be the one to say “that really isn’t appropriate.” which, yes, is so much harder than you think. But also so much easier than you know. It is terrifying to stand up to your friends. They know you, they know your triggers, they know your weaknesses, they always think they can out-debate you. They also know your history and might respond with “I’ve heard you say those words before, yourself.” In which case you can explain that this is something you wished you were able to understand back when you said it. The moment I realized I could say “this isn’t a debate,” was rewarding. You are stronger than you think. And that is so much more important than I knew.

So far, everything made sense to me. Sean’s suggestions were all steps I could follow.

Photo courtesy of Noah Mackenzie

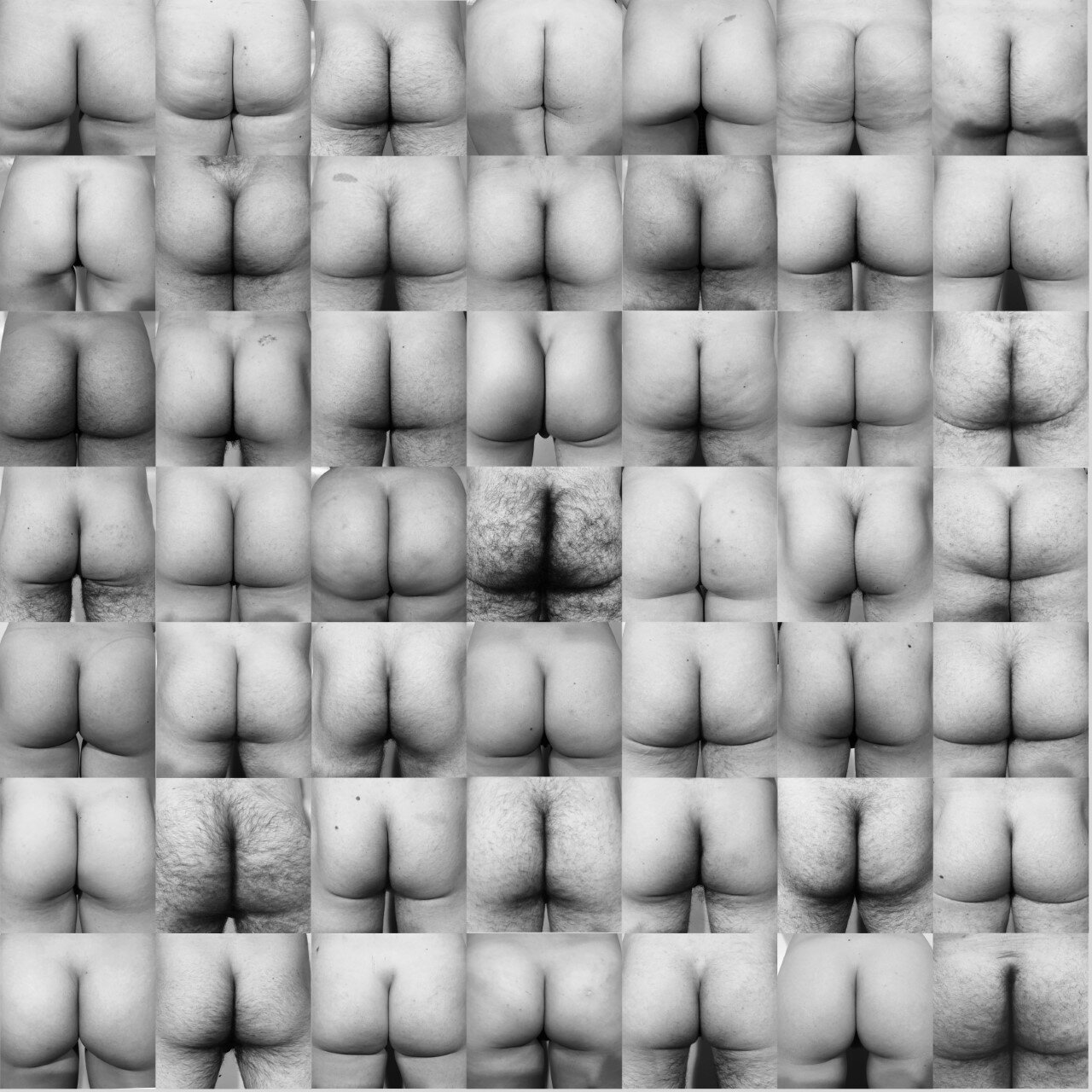

Next, I reached out to my friend, Noah (Insert John Mulaney Joke: His name is also Noah, I’m not friends with myself). Noah is also my age, he studied film and art, and is happily married, congratulations! Noah is tall, blonde, and does amazing body painting work; you can find his art on Instagram @b_oddy. Also, Noah is gay. I mainly mention the body painting projects because of why it came up in our conversation. Noah has been doing artwork in this vein for some time now. I remember back when I was in college he created a collage of bare butts.

Photo courtesy of @b_oddy

So, when I asked him my question, our conversation eventually turned to the subtle reactions Noah perceived from straight men towards gay men. During Noah’s time scouting bodies for his art pieces, he encountered reactions from prospective subjects not far off from “no, that’s gay.” He also mentioned noticing behavioural changes in locker rooms, like how straight men will often cover up with towels when there is someone queer in the space. Those same men will feel comfortable being completely naked when it is perceived to be just other straight men around. Noah explained that he sees these subtle moments, calling the art project “gay” or the lack of comfort in change rooms, as a result of fear.

“To be an ally is to stand by something even if you don’t understand it.” Noah, the interviewee, explained.

That was a point I didn’t immediately agree with, blind following, and it contrasted the topics I discussed with Sean. So I asked him to clarify. I explained that for me, my unbridled support came with the promise that I will get the chance to learn. To understand what I am supporting.

And that’s where I was wrong. His response was a major turning point in my understanding.

A conversation between me and Noah // By: Noah Farberman // THE UNDERGROUND

It’s nobody's job to teach you tolerance when you’re an adult. That’s just something you need to want to learn.

As our conversation continued, Noah brought up some good examples of how being an ally has changed over the years. We talked about Heath Ledger in Brokeback Mountain and how at the time of the film, taking that role was a huge step as an ally. It gave positive queer representation to the world, but moreover, Ledger refused to present at the Oscars when someone made a homophobic joke about the film. In 2018, actor Darren Criss—known for his breakout role as Blaine Anderson, a prominent gay character on the popular television series Glee—was praised for declaring that he will not be taking any more gay roles.

Criss was praised for doing the same thing that Ledger did: being an ally. It almost felt like the rules for being an ally changed right in front of us. The fact is, in 2007 queer representation was low. Heath Ledger didn’t speak for anyone, he gave the queer community a platform, Noah explained to me. Now, the platform is there. Now, when a straight actor claims the role of an effeminate gay character, they are taking that role from an effeminate gay actor who would have less of a chance to get hired in general. Suddenly, what was once providing a platform is now speaking for someone. Noah finished the interview by reiterating his personal belief, while keeping in mind his earlier explanation that it’s alright to ask questions: “it’s not our job to tell YOU how to respect us.”

Photos courtesy of Olivia Stadler

The third person I asked was my close friend Becca. Becca has great hair; I know because everywhere we go their hair gets a million compliments. Becca is also the only person who has ever been able to teach me the word aesthetic in a way I could understand it. Becca came out as gender non-conforming, or non-binary, a few years ago; they came out the day after National Coming Out Day.

Becca’s answer was concise but touched on something that neither Sean nor Noah nor myself had brought up. “It’s okay if you ‘mess up’ sometimes, no one’s perfect, we’re all learning.”

When going through this article for feedback, one of the major comments I received was from my friend Victoria. Victoria also has amazing hair. She’s around my height and consistently the most fashionable person I know.

By: Trevon Smith // THE UNDERGROUND

Victoria believes that it is never okay to mess up, and instead that words and actions can become forgivable when an effort to change is demonstrated. For Victoria, the idea that “it's okay” is closer to an idea of forgiveness. It is never okay to demonstrate a lack of respect towards someone’s identity, but when someone is willing to change their behaviour and in that process of making an actual effort they make a mistake, it can become more forgivable. When it's not a mistake or not from someone willing to change, it just isn’t okay. Whereas for Becca, I believe when they say “It’s okay” it means that “it’s okay,” and that someone recognized their own mistake and apologized profusely before correcting themself.

I chose to include Victoria’s response in this piece because it hit my sentiment perfectly, everyone is going to perceive allyship (and all forms of respect) differently. What might seem like something understandable to one, like mistakenly using the wrong pronoun, has a stronger impact on others. Neither of their versions of allyship is any more ‘correct’, both opinions are equally valid.

“It’s okay if you ‘mess up’ sometimes, no one’s perfect, we’re all learning.” Becca’s words repeated in my head.

It’s a brief sentiment but an impactful one. And it helps me easily segue into the collective notion I accumulated from all four of the friends that I spoke to for this article, but also from the comedy community, my university community, writing community, and from so many friends I hold close: change and growth are linked to time. Adapting is essential. We all need to keep learning.

These are my findings from those four interviews. I found that for one person, being an ally means fighting a war on behalf of someone else. For another it means treating everyone with the same comfort, respect, professionalism. It might mean thinking before you speak and always being aware of your impact, for one, and for someone else it just means demonstrating a willingness to learn.

But that is only four people. And no community can be represented by any one person. This is always going to be a personal discussion. Everyone has their own perception of respect and the best thing you can do is listen. Listen when someone tells you their pronouns—it’s not a debate, it is truth. Take it as such. Listen when someone explains how your actions or words hurt them. An apology is never about making yourself feel better; some of the best apologies I’ve received are the ones I can’t accept.

Although respect will change from person to person, I should definitely say, there are some universal truths; I won’t list them all but I will let Wanda Sykes explain this easy one to learn.